Calcium stones are also associated with hyperoxaluria (ie: too much oxalate in the urine), as well as hyperuricosuria (ie: too much uric acid in urine), and hypocitraturia (ie: too little citrate in the urine).

The second most common type of stone is a struvite stone. A struvite stone is composed of magnesium, ammonium, and phosphate. They form during kidney infections when the "bug" responsible for the infection is a urease spliting bacteria such as proteus vulgaris. These bacteria are capable of producing ammonium from urea. In large enough quantities the ammonium can combine with magnesium and phosphate to form a struvite stone. These stones can be large and in the shape of the draining system of the kidney (ie: calyces); when the have this appearance they are referred to as "staghorn calculi".

Uric acid stones are produced under conditions of high amounts of uric acid in the blood and urine (ie: gout or conditions where cell death is high such as in leukemias and other cancers). Some patients lack elevated levels of uric acid in the blood or urine. However, they are still capable of forming uric acid stones, especially if their urine is acidic. This is because urate precipitates in acidic environments.

Finally, cystine stones form because of certain genetic conditions. The cells that line the urinary tract are normally able to re-absorb amino acids like cysteine. However, certain genetic mutations cause abnormalities in the ability of these cells to transport cysteine from the urine back into the blood. The resultant increase in cysteine in the urine can cause cystine stones to form.

Signs and Symptoms

A fair number of kidney stones are asymptomatic. However, occasionally a stone will pass from the kidney to the bladder through a narrow tube called the ureter. This can produce excruciating pain that is located in the flank region. Sometimes the pain can be referred to the scrotum in males, or labia majora in women.

In addition, sometimes the urine will have blood in it from irritation of the urinary tract. If there is enough blood, the urine will turn pink; although, microscopic hematuria (ie: blood in the urine that can only be picked up by lab testing) can also occur.

Complications

There are several worrisome complications of kidney stones. They include hydronephrosis and pyelonephritis. Hydronephrosis refers to dilation of the urinary tract secondary to blocked urine and increased pressures. The increased pressure is reverberated all the way to the filtration unit of the kidney, the glomerulus. If high enough pressures are reached, irreversible kidney damage can occur leading to chronic kidney disease and renal failure.

Pyelonephritis is a fancy term for an infected kidney. The irritation caused by the stones provides a suitable environment for bacteria to proliferate. These infections can be life threatening, and like hydronephrosis, can lead to irreversible kidney damage and renal failure.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of kidney stones is made by looking at urine under the microscope. This is known as urine microscopy. Different types of stones have different appearances (see images above), but more importantly also have different treatments.

In addition, a urine analysis is often performed in order to determine the pH. Urine electrolytes including calcium, magnesium, sodium, etc. are also sent, and can be helpful in determining the type of stone.

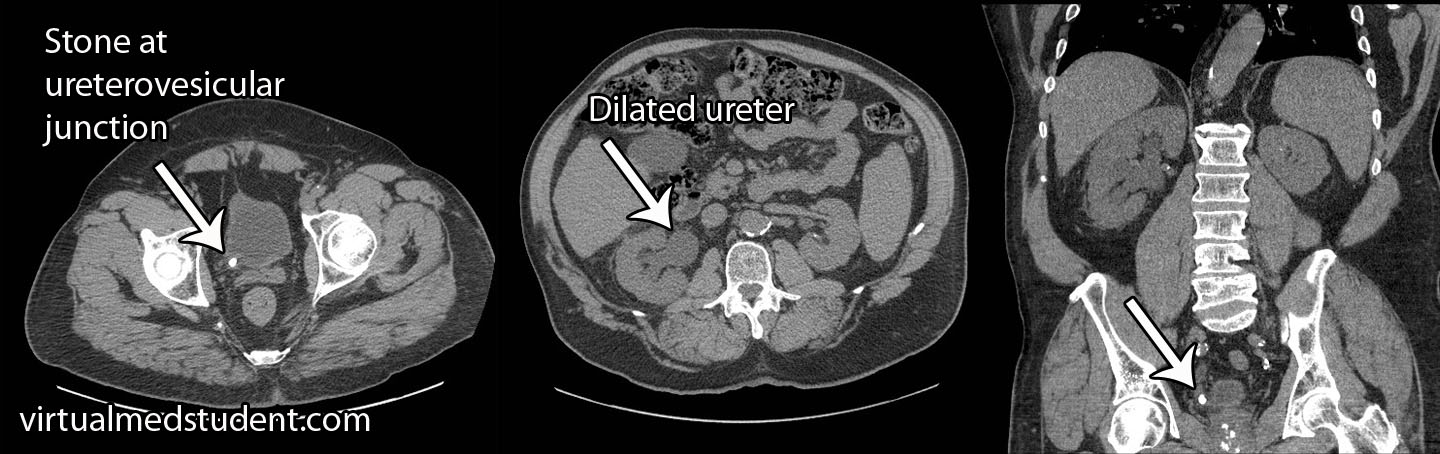

Imaging studies are also commonly done. The quickest, cheapest, and most readily available is an ultrasound of the kidney. If stones are present they can cast shadows (similar to the ones gallstones cast), which are picked up by the ultrasound machine. CT scans of the kidney can also show stones. Occasionally a procedure known as intravenous pyelography (IVP) is done. In IVP, radio-opaque dye is injected into the veins. It ultimately gets filtered and excreted by the kidneys, at which point an X-ray is taken; the X-ray can provide information about stones if they are present.

Treatment

The treatment of kidney stones depends in part on the size of the stone, as well as the type. Stones that contain large amounts of calcium cannot be dissolved with current medicines available; uric acid and cysteine stones can. Medical therapy is designed to either (a) dissolve the stone, or (b) get it to pass with minimal amounts of discomfort.

Expulsive therapy involves using medications to relax the smooth muscles around the "tubes" (ie: ureter, urethra) of the urinary tract. Commonly used medications that do this include:

(1) Alpha-blockers (ie: tamsulosin, terazosin, etc.)

(2) Calcium channel blockers (ie: nifedipine)

These medications help stones pass, especially when they are larger than 3mm in size. In addition, medications for controlling pain associated with kidney stones are paramount to ensuring stone expulsion.

Stones that are larger than 8mm in diameter usually do not pass on their own, even with medical expulsive therapies. These stones must be managed through mechanical or surgical means.

The first approach is to break the stones into smaller fragments using a technology called extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy. This is a non-invasive method that delivers powerful waves through the body designed to fragment the stone. The second, and more invasive, procedure is ureteroscopy. This refers to placing a tiny camera into the urethra, bladder, and ultimately into the ureter in order to directly visualize the stone. It is then removed with small forceps.

Staghorn calculi larger than 4 cm diameter require a procedure known as percutaneous nephrolithotomy. In essence, a tube is placed through the skin into the kidney. From there the stone can be directly visualized and removed.

Preventing stones from re-forming is also important. Adequate hydration is critical in preventing all stone types, and is probably the single most important preventative measure! Hydration ensures that urine output is high enough to prevent precipitation of minerals that commonly cause stones.

(1) adequate hydration

(2) low sodium diet

(3) low protein diet

(4) low oxalate diet

(5) normal or high

calcium diet

Treatment for specific types of stones are also given. To prevent the re-formation of uric acid stones, potassium citrate is commonly given to make the urine less acidic (more alkaline). This increases the solubility of urate and keeps it from precipitating into a stone.

Overview

Kidney stones come in different shapes and sizes. The most common type are calcium stones. Many patients are asymptomatic although flank pain that radiates into the scrotum and labia majora are common. Blood tinged urine may also be seen. Diagnosis is based on urine microscopy, kidney ultrasound, CT scan, and urinalysis. Treatment for all kidney stones consists of adequate hydration and analgesics. Stones larger than 8mm often need to be broken up or removed via mechanical means.

Related Articles

References and Resources

- Caudarella R, Vescini F. Urinary citrate and renal stone disease: the preventive role of alkali citrate treatment. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2009 Sep;81(3):182-7.

- Goldfarb DS. In the clinic. Nephrolithiasis. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Aug 4;151(3):ITC2.

- Worcester EM, Coe FL. Clinical practice. Calcium kidney stones. N Engl J Med. 2010 Sep 2;363(10):954-63.

- Coe FL, Evan AP, Worcester EM, et al. Three pathways for human kidney stone formation. Urol Res. 2010 Jun;38(3):147-60. Epub 2010 Apr 22.

- Leighton TG, Cleveland RO. Lithotripsy. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 2010;224(2):317-42.