Atlanto-occipital dislocations (AODs) occur when there is severe damage to the ligaments that connect the skull to the cervical spine. The most common cause of an AOD is trauma.

There are several classifications of atlanto-occipital dislocations. In type 1 dislocations the base of the skull moves anteriorly (ie: forward) relative to the dens of the second cervical vertebrae. In type 2 dislocations the skull moves superiorly (ie: upwards) relative to the cervical spine. In type 3 dislocations the skull moves posteriorly (ie: backwards) relative to the cervical spine.

Often times more than one classification may exist in a single patient. For example, a patient may have both a type 1 and type 2 AOD if the patient’s skull has moved forward and upwards relative to the cervical spine.

Signs and Symptoms

Most cases of complete atlanto-occipital dislocation are fatal. Severe damage to the spinal cord around the cranio-cervical junction leads to respiratory paralysis and death if mechanical ventilation is not started rapidly. Patients are often quadriplegic (ie: unable to move their upper and lower extremities) because of damage to the descending motor axons of the corticospinal tract. Incomplete injuries can also occur with varying degrees of cervical spine injury.

The lower cranial nerves are sometimes involved in the injured segment. The most commonly injured cranial nerves are the abducens (VI), vagus (X), and hypoglossal (XII) nerves. Abducens nerve injury causes an inability to deviate the eye outwards. Damage to the hypoglossal nerve causes deviation of the tongue towards the side of the injured nerve (“lick your wound”).

Surprisingly, some patients with atlanto-occipital dislocation may have no neurologic symptoms! It is therefore important to rule out ligamentous injury, especially in patients who have had severe head and neck trauma.

Diagnosis and Classification

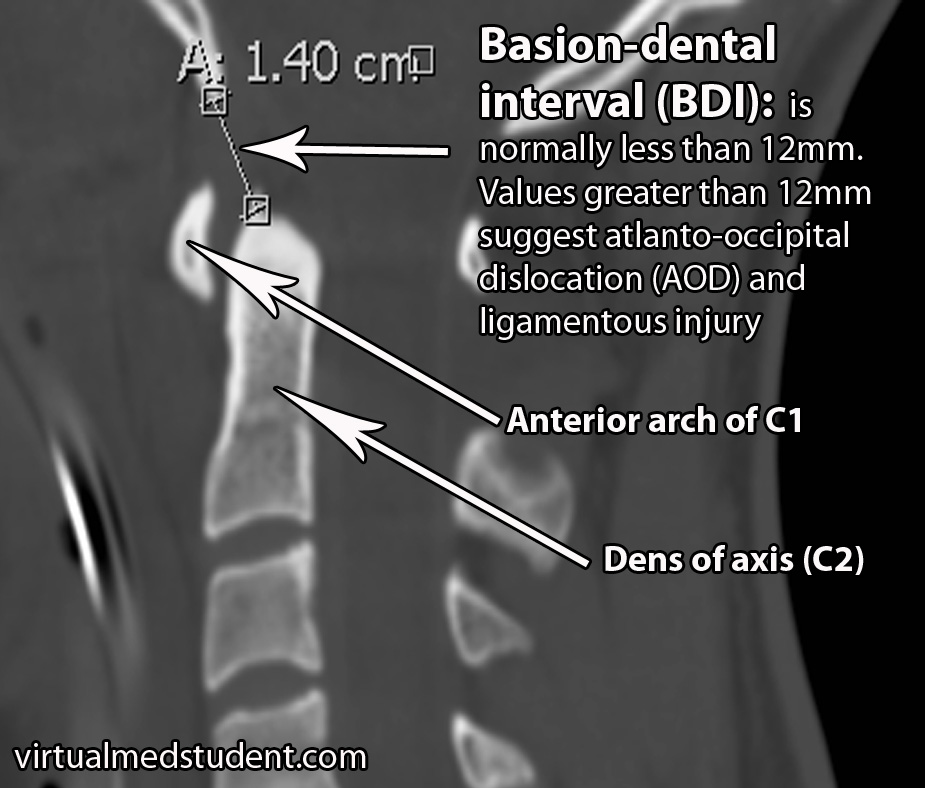

There are several methods for determining if atlanto-occipital dislocation has occurred. The first is the “BAI-BDI method”. Two distances are measured. The BDI, or basion-dental interval, measures the distance between the most anterior and inferior portion of the skull (ie: “basion”) and the tip of the dens, which is a superior extension of the second cervical vertebrae. The BDI should normally be less than 12mm. In the image below the BDI is 14mm and is indicative of atlanto-occipital dislocation.

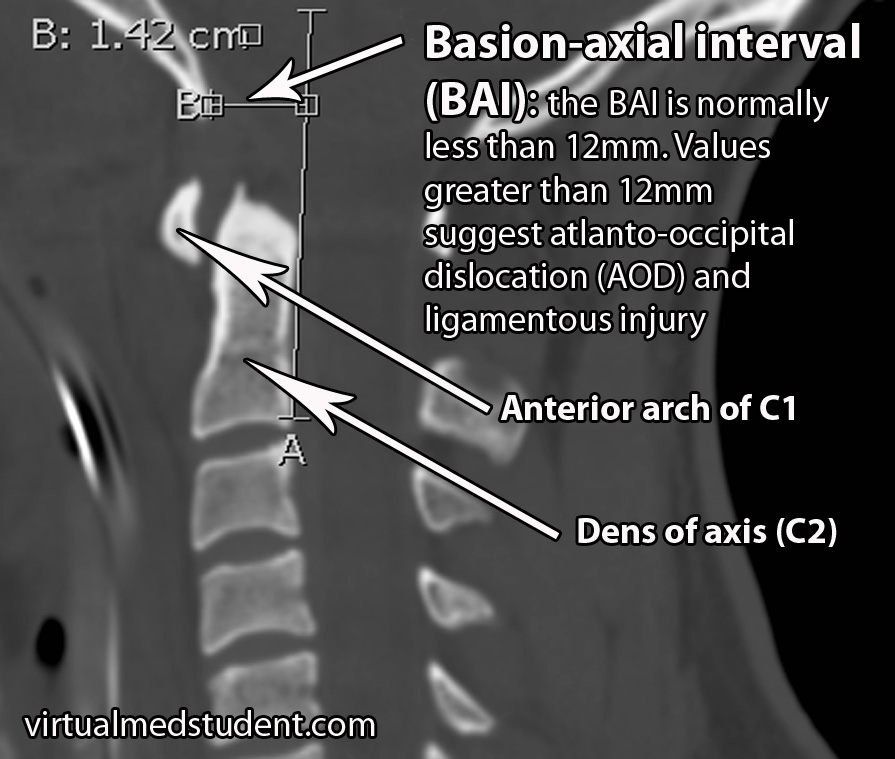

The second distance that is measured is the BAI, or basion-axial interval. The BAI is the distance between the basion and a line drawn straight up from the posterior (ie: back) portion of the dens. The normal interval is less than 12mm. In the image below the BAI is 14.2mm indicating likely atlanto-occipital dislocation.

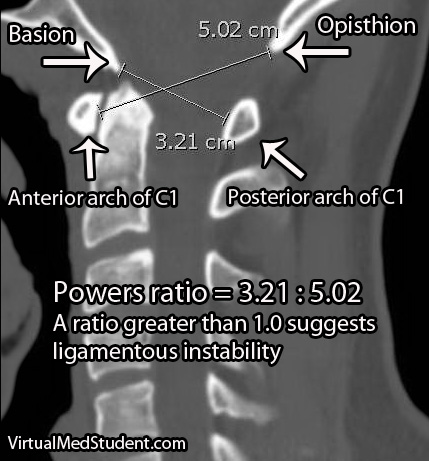

A second method of assessing atlanto-occipital dislocation is known as Power’s ratio. Power’s ratio is most useful if the dislocation is anterior (ie: the head moves forward relative to the spine). Two distances are measured. The first is the distance between the opisthion and the anterior ring of C1; the second is the distance between the basion and the posterior ring of C1. The second distance is then divided by the first to obtain the ratio. A “normal” ratio is less than 1.0; if the ratio is greater than 1.0 then suspicion for dislocation should be high.

X-rays and CT show bony anatomy very well, but do not demonstrate ligamentous injury. Many patients with suspected AOD may also get an MRI to assess ligamentous damage. MRI will usually show severe injury to the ligaments that connect the first and second cervical vertebrae to the skull base.

There are two commonly used classification systems for describing atlanto-occipital dislocations. The Traynelis system is purely descriptive and is based on which way the head moves relative to the spine.

| Traynelis Classification | |

| Type 1 | Head moves forward relative to the spine |

| Type 2 | Head moves upwards relative to the spine |

| Type 3 | Head moves backwards relative to the spine |

The Bellabarba system is based on CT findings and is used to determine stability; it is also useful because it helps guide treatment decisions. A stable injury is one in which the dislocation is within 2mm of a normal BDI/BAI value and does not get worse with a traction test. Unstable injuries are present when the dislocation gets worse with a traction test; these injuries may be reduced at baseline (ie: within 2mm of a normal BDI/BAI) or grossly abnormal. That being said, it is important to note that very few doctors perform traction tests in patients with suspected AOD as this can worsen the condition!

| Bellabarba Classification | ||

| Type | Description | Stability |

| Type 1 | Alignment within 2mm of normal BAI/BDI interval; distracts less than 2mm with traction | Stable |

| Type 2 | Reduced at baseline (ie: within 2mm of normal BDI/BAI), but significant distraction with traction test | Unstable |

| Type 3 | Severely misaligned relative to normal BDI/BAI values | Unstable |

Treatment

Treatment of atlanto-occipital dislocations involves spinal immobilization. This is usually done via a surgical procedure known as an occipital-cervical fusion in which the back of the skull is fused to the cervical spine. Some patients are also put in a halo immobilization device.

Overview

Atlanto-occipital dislocation occurs after severe injury to the ligaments that connect the skull to the cervical spine. It most commonly occurs after severe head or neck trauma. Death secondary to ventilatory failure, quadriplegia, and cranial nerve deficits are common symptoms. Diagnosis is based on characteristic findings found on CT, x-rays, and MRI scans. Treatment is with spinal immobilization, either with a halo apparatus, or a surgical procedure known as occipital-cervical fusion.

Some More Useful Learning Material…

- Cervical Facet Dislocation: Houston We Have a Problem

- Atlas Fractures: The Weight of the World on Its Shoulders

- Latin for Toothlike: Fractures of the Odontoid Process (Dens Fractures)

- The Hangman’s Fracture

References and Resources

- Garrett M, Consiglieri G, Kakarla UK, et al. Occipitoatlantal dislocation. Neurosurgery. 2010 Mar;66(3 Suppl):48-55.

- Greenberg MS. Handbook of Neurosurgery. Sixth Edition. New York: Thieme, 2006. Chapter 25.

- Deliganis AV, Mann FA, Grady MS. Rapid diagnosis and treatment of a traumatic atlantooccipital dissociation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998 Oct;171(4):986.

- Traynelis VC, Marano GD, Dunker RO, et al. Traumatic atlanto-occipital dislocation. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1986 Dec;65(6):863-70.

- Bellabarba C, Mirza SK, West GA, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of craniocervical dislocation in a series of 17 consecutive survivors during an 8-year period. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006 Jun;4(6):429-40.

- Horn EM, Feiz-Erfan I, Lekovic GP, et al. Survivors of occipitoatlantal dislocation injuries: imaging and clinical correlates. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007 Feb;6(2):113-20.