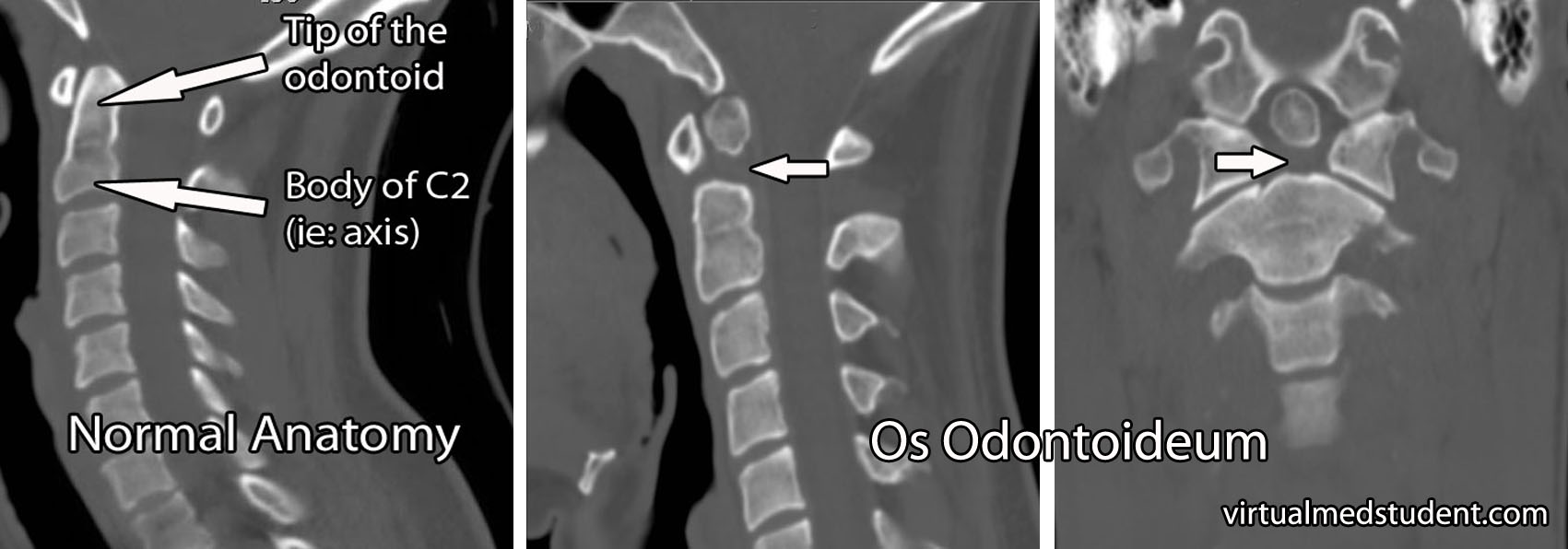

In order to understand what an os odontoideum is, we have to first appreciate the anatomy of the first two cervical vertebrae.

The first cervical vertebrae is known as the "atlas". It forms joints with the base of the skull and the second cervical vertebrae, which is also known as the axis. It has a an elongated structure on its ventral aspect called the “odontoid”. The odontoid of the axis connects to the atlas via numerous ligaments. This joint provides most of the flexibility that allows you to move your head in various directions.

An os odontoideum is a failure of the tip of the odontoid (ie: the part closest to the atlas) to fuse with its base on the axis.

Exactly why this occurs is still debated. The first theory is that it represents a congenital failure of the odontoid to fuse properly with the axis. The second, and more supported theory is that it may be caused by a previous fracture in early childhood that failed to heal properly. Regardless of the cause, the end result is a floating mass of bone that represents the superior (ie: top) most portion of the odontoid process.

This mass of bone may be fused to the base of the skull. If this is the case, the term "dystopic" os odontoideum is used. Or it may articulate and move with the atlas; if this is the case, the term "orthotopic" os odontoideum is used.

Signs and Symptoms

Many patients with os odontoideum are asymptomatic. However, because the tip of the odontoid is not technically connected to the base of the axis the patient may have an unstable neck. If the instability is severe, damage to the spinal cord can result causing myelopathy.

Myelopathy can manifest with several symptoms. Patients may have numbness and tingling in the upper and lower extremities. If damage to the nervous tissue responsible for motor movements occurs, patients may complain of weakness (and possibly even paralysis in extreme cases!).

On examination, patients may have both upper and lower motor neuron signs. Upper motor neuron signs refer to exaggerated reflexes – Babinski and Hoffmann signs, and clonus are all examples of this. These findings tend to be seen below the level of the actual spinal cord injury. Lower motor neuron findings typically occur at the level of the spinal cord damage, and consist of flaccid weakness with decreased reflexes.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of os odontoideum is made by x-rays or CT of the cervical spine. To assess the degree of instability in the joint, some doctors will get flexion and extension x-rays as well.

The image to the right is a CT of the cervical spine that illustrates the missing portion of the odontoid process (marked by arrows in the image). A normal CT of the cervical spine is shown to the left for comparison.

Some patients may also get an MRI to assess for spinal cord and ligamentous injury, especially when symptoms or physical examination findings are present.

Treatment

Treatment depends on whether or not symptoms are present, and whether or not the cervical spine is unstable. Many patients without symptoms may be followed with serial X-rays or CT scans to assess for progression of instability.

If significant instability exists, or the patient has signs and symptoms consistent with spinal cord injury, then surgical stabilization is performed. There are numerous ways to achieve stabilization in this region surgically, which are outside the scope of this article. Regardless of which method is used, the end result is stabilization of the joint between the first and second cervical vertebrae.

Overview

Os odontoideum is an absence of part of the odontoid process. It may be due to a congenital malformation, or an early childhood fracture that fails to heal properly. Symptoms, when present, are due to spinal cord injury (ie: myelopathy) and consist of weakness, numbness, tingling, and other signs of spinal cord dysfunction. Imaging with x-rays or CT scan can show the bony defect. MRI is occasionally used to assess the spinal cord itself. Treatment depends on whether or not symptoms or significant instability is present. The best treatment options are surgical stabilization of the joint between C1 and C2 using one of several potential methods.

Related Articles

- Dislocated facet joints

- Thoracolumbar burst fractures

- Spondylolysis

- Odontoid fractures

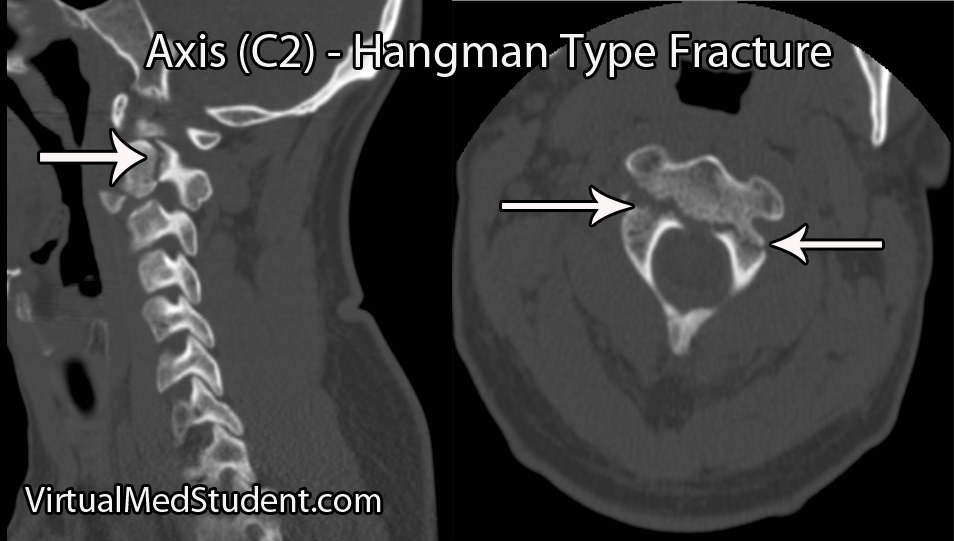

- Hangman’s fracture

- Atlas fracture

References and Resources

- Arvin B, Fournier-Gosselin MP, Fehlings MG. Os odontoideum: etiology and surgical management. Neurosurgery. 2010 Mar;66(3 Suppl):22-31.

- Klimo P Jr, Kan P, Rao G, et al. Os odontoideum: presentation, diagnosis, and treatment in a series of 78 patients. J Neurosurg Spine. Oct 2008;9(4):332-42

- Fielding JW, Griffin PP. Os odontoideum: an acquired lesion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Jan 1974;56(1):187-90.

- Gwinn J, Smith J. Acquired and congenital absence of the odontoid process. AJR. 1962;88:424-31.

- reenberg MS. Handbook of Neurosurgery

. Sixth Edition. New York: Thieme, 2006. Chapter 25.

- Harms J, Melcher RP. Posterior C1-C2 fusion with polyaxial screw and rod fixation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001 Nov 15;26(22):2467-71.

- Arvin B, Fournier-Gosselin MP, Fehlings MG. Os Odontoideum: Etiology and Surgical Management.