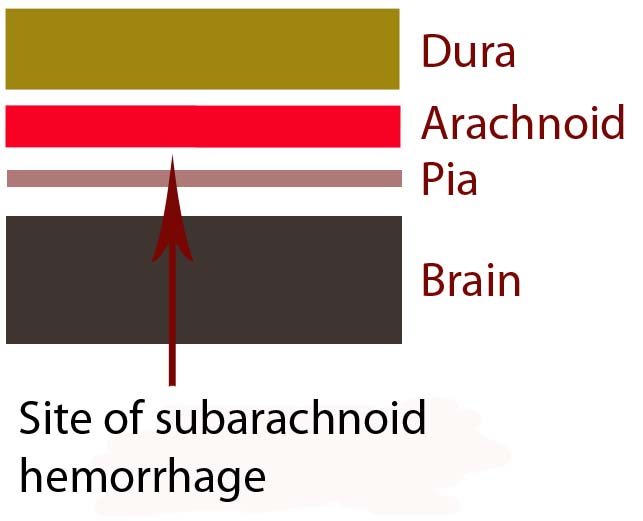

In order to understand subarachnoid hemorrhage we have to first appreciate the layers that make up the brain and its surrounding tissues. The brain itself has three protective layers: dura mater, the arachnoid, and the pia.

The dura is a thick layer of fibrous tissue immediately below the skull. Below the dura is the arachnoid, which is a layer of delicate web-like tissue (hence the name "arachnoid"). Finally, below the arachnoid is the pia mater. The pia is a very thin layer that is directly adjacent to brain tissue.

The subarachnoid space, or the region between the arachnoid tissue and the pia contains cerebrospinal fluid, which acts like a liquid shock absorber for the brain. Also contained within the subarachnoid space are blood vessels that penetrate down into the brain tissue. Sometimes these blood vessels "leak", which can cause a "sub-arachnoid" hemorrhage.

The most common cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage is traumatic injury; the most common non-traumatic cause is a ruptured aneurysm.

An aneurysm is an abnormal ballooning out of a blood vessel’s wall. The balloon’s dome is much weaker than the rest of the vessel wall. These weak areas can rupture allowing blood to leak out of into the subarachnoid space.

Other causes of subarachnoid hemorrhage include idiopathic (ie: unknown) causes, arteriovenous malformations, vessel dissections, and very rarely tumors. Regardless of the cause, blood will pool in the subarachnoid space.

The remainder of this article will focus on the most common non-traumatic cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage – aneurysm rupture.

Signs and Symptoms

The classic symptom of a subarachnoid hemorrhage is a horrific headache described as the “worst headache of their life". Photophobia, nausea, vomiting, and nuchal rigidity are also common. Seizures may also occur. In addition, depending on how severe the subarachnoid hemorrhage is, patients may have decreased levels of consciousness; some patients become comatose, and many die before reaching medical attention.

The patient’s clinical status is graded according to the Hunt and Hess system. It only applies to patients in whom subarachnoid hemorrhage is caused by rupture of an aneurysm. This grading system was initially established to help determine mortality and clinical outcomes. In modern practice, these numbers are likely high given modern improvements in critical care and neurosurgical intervention since Hunt and Hess first developed their grading system.

| Hunt and Hess Clinical Grading Scale | ||

|---|---|---|

| Grade | Patient’s Clinical Status | Associated Mortality |

| 1 | Mild headache and/or nuchal rigidity | 1% |

| 2 | Cranial nerve dysfunction, moderate to severe headache and/or nuchal rigidity | 5% |

| 3 | Mild focal neurological deficit, lethargic, confused | 19% |

| 4 | Stuporous, moderate to severe hemiparesis, early decerebrate posturing | 40% |

| 5 | Coma, decerebrate posturing | 77% |

The world federation of neurological surgeons also has a clinical score based on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). It associates the patient’s GCS with the likelihood of death.

| World Federation of Neurological Surgeons Grading System | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| GCS | Major focal deficit | Mortality | |

| 1 | 15 | No | 5% |

| 2 | 13-14 | No | 9% |

| 3 | 13-14 | Yes or No | 20% |

| 4 | 7-12 | Yes or No | 33% |

| 5 | 3-6 | Yes or No | 77% |

It is very important to think about the possibility of subarachnoid hemorrhage in patients presenting with these signs and symptoms. Prompt diagnosis and treatment is necessary in order to prevent devastating consequences!

Complications

Blood in the subarachnoid space is very irritating to the brain and cerebral blood vessels. Because of this, several complications can occur.

One of the most common complications is known as "vasospasm." Vasospasm occurs when the blood vessels of the brain spasm several days after the initial hemorrhage. When this occurs blood is no longer able to flow past the blockage; if this occurs for a long enough period of time a stroke can occur. The peak period for vasospasm occurs between 3 and 14 days after the initial bleed.

Another complication of subarachnoid hemorrhage is known as cerebral salt wasting. This occurs when a patient urinates excessive amounts of sodium causing the blood level of sodium to drop precipitously. Because of the excessive urination the patient also becomes dehydrated. Aggressive fluid and salt resuscitation must be given to prevent profound hyponatremia (ie: decreased sodium levels in the blood), which can cause seizures, coma, and death.

In addition, for unknown reasons, many patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage also shower their cerebral hemispheres with micro-thrombi (ie: clots), which can lead to many small strokes. The reason why patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage become coagulopathic is still an area of intense research.

Diagnosis

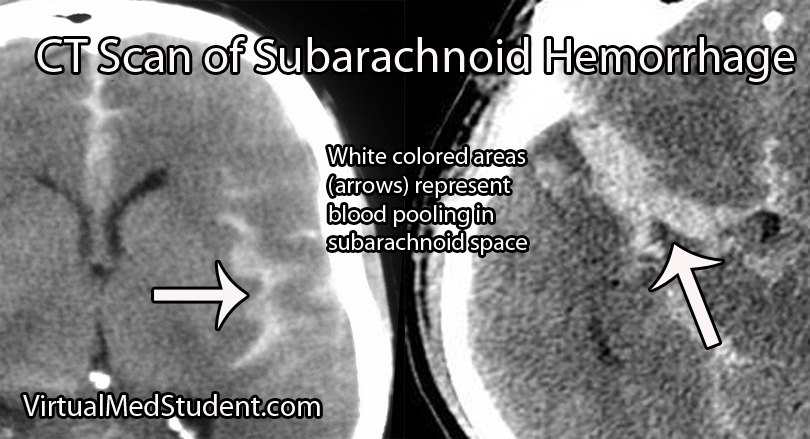

Subarachnoid hemorrhage is most commonly diagnosed by head CT. CT scans are fast and readily pick up the extravasated blood, which layers in the subarachnoid space (see image below). If there is a high clinical index of suspicion but CT of the head is negative than a lumbar puncture should be performed. If the spinal fluid has xanthochromima (a product of red blood cell breakdown) this is highly concerning for subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage is not a diagnosis per say, but rather the result of some underlying pathology (ie: aneurysm, trauma, etc.). Many of these pathologies are treatable; therefore, it is important to figure out what caused the subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Since many are the result of ruptured aneurysms there are several other tests that are often done. The first test is a CT angiogram (CTA). In this test a radio-opaque material is injected into the blood vessels and a CT is performed.

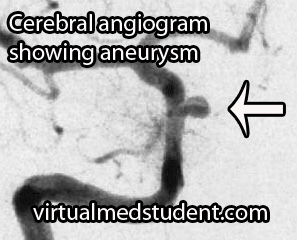

A more invasive procedure known as a "cerebral angiogram" (image to the right) is also often performed.

In this test, a catheter is inserted into blood vessels in the groin and then threaded up into the blood vessels of the brain. Radio-opaque material is injected and x-rays can pick up abnormalities in the vessel.

The benefit of doing a cerebral angiogram is that it is diagnostic, and treatment can frequently be offered through the catheter itself.

Treatment

There are three main components of treating a subarachnoid hemorrhage: treating the underlying cause, preventing a "re-bleed", and preventing secondary complications.

Since many subarachnoid hemorrhages are caused by aneurysm rupture we’ll discuss the treatment for this common cause. Aneurysms are treated either “open” or “closed”.

“Open” refers to a surgical procedure in which part of the skull is removed. The surgeon then dissects down to the aneurysm. Once identified, a clip is placed around the neck of the aneurysm (ie: you can think of the clip as putting a knot in the neck of a balloon). This stops blood from flowing into the aneurysm, and therefore prevents re-rupture.

“Closed” treatment refers to endovascular technology in which a small micro-catheter is threaded from the blood vessels in the groin into the cerebral vasculature. The aneurysm is located via angiogram. Through a hole in the microcatheter tip the physician then fills the aneurysm dome with small metallic coils.

Once blood is in the subarachnoid space secondary complications often result. One of these complications is referred to as "vasospasm". Medications such as oral nimodipine and intra-arterial nifedipine are used to reduce the amount of vasospasm by inhibiting smooth muscle contraction in the wall of the blood vessel.

Overview

Subarachnoid hemorrhage occurs most commonly after an intracerebral aneurysm ruptures, although other causes exist. Regardless of the cause, blood spills out into the subarachnoid space. Symptoms include a horrible headache, focal neurological deficits (ie: weakness, difficulty speaking, etc.), and coma. If an aneurysm is the cause, it is secured with clipping or coiling. Preventing secondary complications such as vasospasm is also an important component of treatment.

References and Resources

- Hunt WE, Hess RM. Surgical Risk as Related to Time of Intervention in the Repair of Intracranial Aneurysms. Journal of Neurosurgery 1968; 28:14-20.

- Report of World Federation of Neurological Surgeons Committee on a Universal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Grading Scale. Journal of Neurosurgery 1988; 68:985-986.

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease

. Seventh Edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2004.

- Greenberg MS. Handbook of Neurosurgery

. Sixth Edition. New York: Thieme, 2006. Chapter 25.

- Frontera JA. Decision Making in Neurocritical Care

. First Edition. New York: Thieme, 2009.