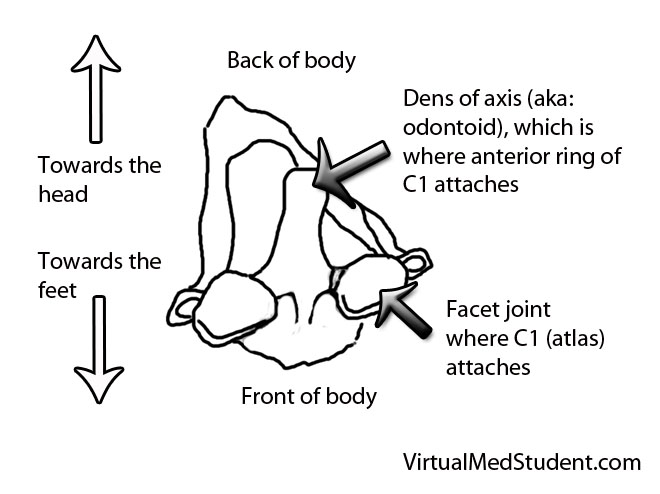

The odontoid process (also know as the "dens") is the finger of bone that sticks up from the second cervical vertebrae (ie: the axis).

It articulates via numerous ligaments to the anterior arch/ring of the first cervical vertebrae (ie: the atlas) to form a joint. This joint is what allows you to rotate your head from side to side as if you were nodding “no”.

Fractures of the odontoid typically occur after traumatic events. In younger, otherwise healthy individuals tremendous force is necessary to fracture the odontoid. Breaks are typically seen after car, motorcycle, or sporting accidents. In older, osteoporotic people simple ground level falls can result in a fracture. Less commonly, fractures of the odontoid may be caused by tumor chipping away at the underlying bone (a so called “pathologic” fracture).

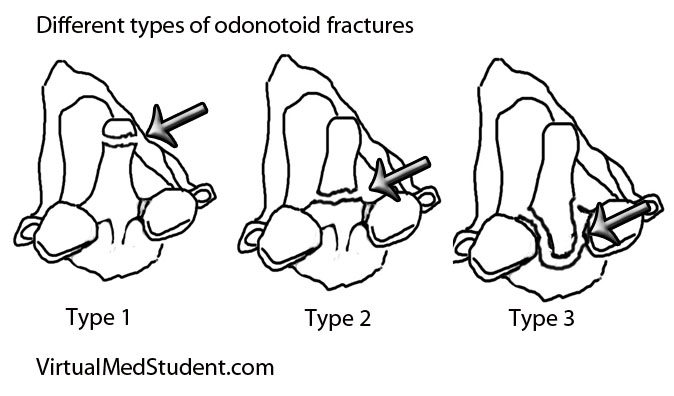

Since the odontoid is a relatively long piece of bone it can fracture at one of several distinct sites. The most commonly used system (Anderson and D’Alonzo) categorizes fractures into one of three types:

- Type 1 – a fracture at the tip of the odontoid.

- Type 2 – a fracture at the base of the odontoid.

- Type 3 – a fracture involving the body of the C2 vertebrae, which includes the odontoid within it.

This grading system is important because it helps predict both stability of the C1-C2 (ie: atlanto-axial) joint and guides potential treatment options.

Signs and Symptoms

Roughly 80% of patients with odontoid fractures do not have any neurological injury to their spinal cord. The remaining patients can exhibit anything from quadriplegia to mild sensory disturbances. Patients with severe cervical spinal cord injury usually are unable to breath (secondary to diaphragm paralysis) and frequently die at the scene of the accident.

Many patients with odontoid fractures will have significant neck pain that radiates up into the scalp. This is usually caused by neck muscles spasming secondary to the injury.

Diagnosis

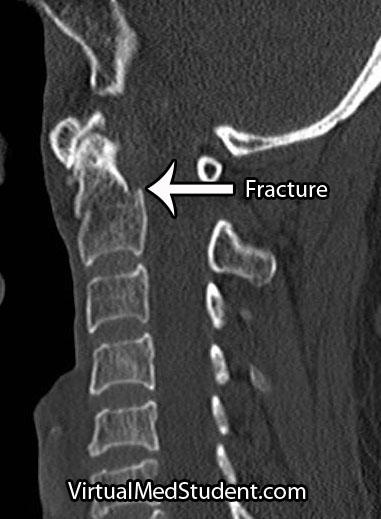

CT scans, x-rays, and MRIs are all useful in diagnosing and properly treating odontoid fractures.

CT scans of the cervical spine provide excellent bony detail, and also help illustrate any additional fractures that may be present.

MRI of the cervical spine is useful for assessing any co-existent ligamentous injury. If ligamentous injury is present it drastically alters treatment decisions.

Treatment

Treatment of odontoid fractures is based on both bony and ligamentous injury. The goal of treatment is to stabilize the spine either by allowing the bone to heal on its own, or by fusing the spine artificially using rods, screws, and/or wires.

Placement of an odontoid screw is one method of fixing non-displaced type II fractures. However there are numerous contraindications for odontoid screw placement. For example severe angulation of the fractured segment precludes placement of a screw; barrel chested anatomy prevents an adequate angle for screw trajectory in the operating room. In addition, if the transverse ligament is disrupted, bony fixation with an odontoid screw alone will not stabilize the joint.

Approaching the spine from behind is another option to stabilize odontoid fractures. Fusing the atlas (C1) to C2 or C3 is sometimes used if odontoid screw placement cannot be performed and the injury is deemed unstable. It is important to note that posterior approaches can restrict motion, especially in the high cervical spine.

Non-surgical options must ensure that the patient has minimal to no movement of the neck in order to give the bone an adequate chance to heal on its own. Rigid collars or halos are used to prevent neck motion.

Overview

Odontoid fractures come in three flavors depending on the location of the fracture. Symptoms can be anything from mild neck discomfort to quadriplegia, although neurological injury is surprisingly uncommon. Diagnosis is based on CT and MRI. Treatment is with cervical immobilization for an extended period of time, or surgical fusion. Treatment decisions are based on the degree of both bony and ligamentous injury, as well as the patient’s overall health status.

Related Articles

References and Resources

- Hsu WK, Anderson PA. Odontoid fractures: update on management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010 Jul;18(7):383-94.

- Harrop JS, Hart R, Anderson PA. Optimal treatment options for odontoid fractures in the elderly. Spine (Phila PA 1976). 2010 Oct 1;35(21 Supplem):S219-27.

- Anderson LD, D’Alonzo RT. Fractures of the odontoid process of the axis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974 Dec;56(8):1663-74.

- Greenberg MS. Handbook of Neurosurgery

. Sixth Edition. New York: Thieme, 2006. Chapter 25.