Parkinson’s disease is caused by the death of neurons in a part of the brain known as the substantia nigra.

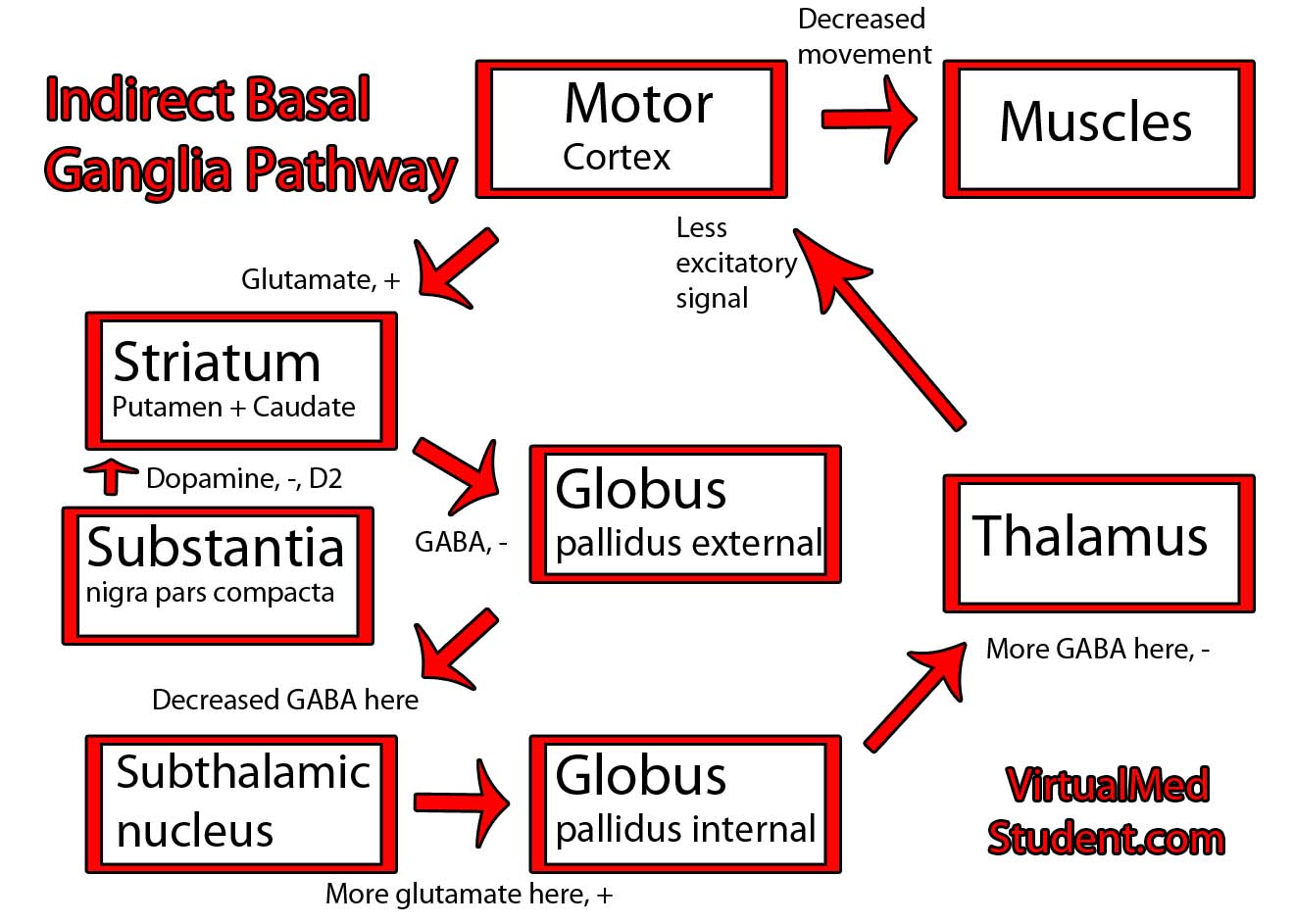

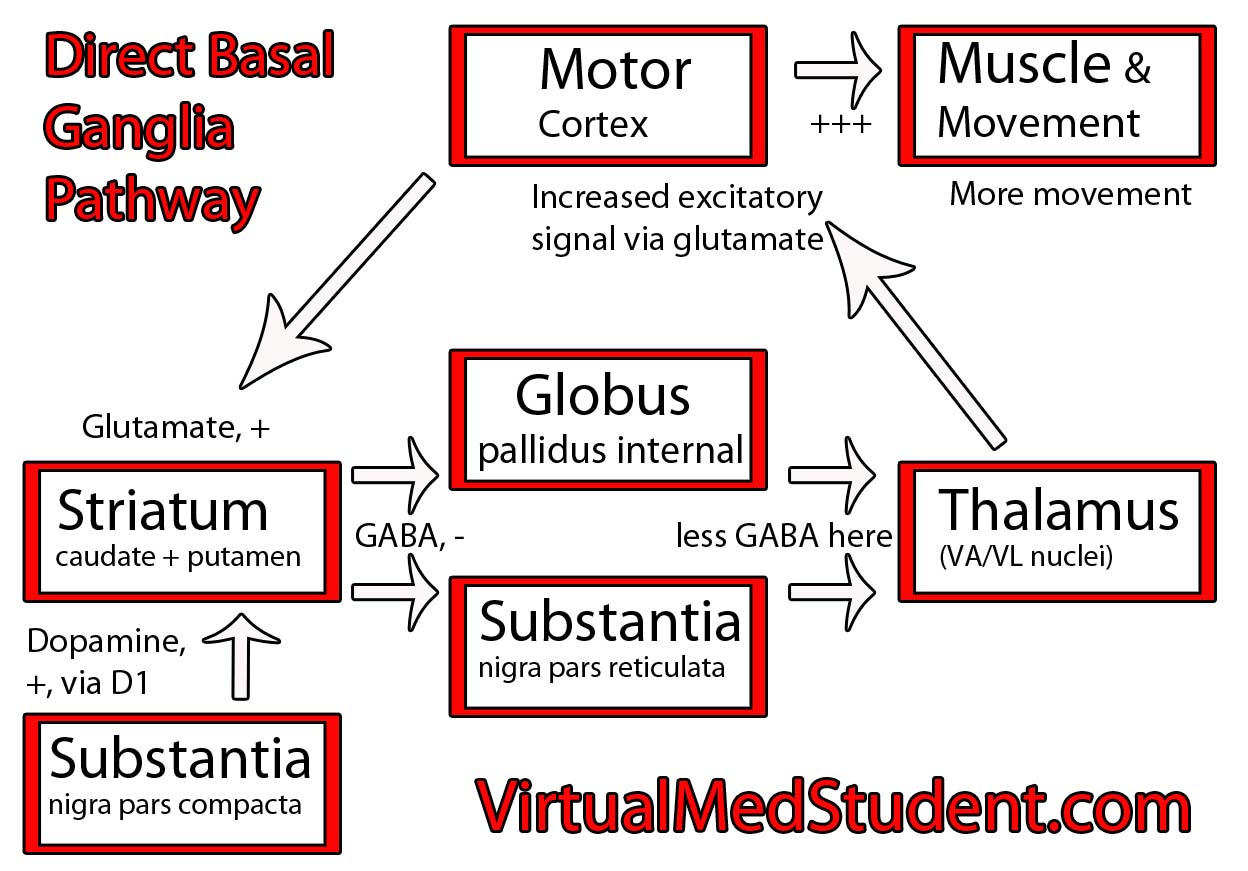

The substantia nigra is part of a system of connected neurons known collectively as the basal ganglia. This system is very important in the control of movement. The substantia nigra contains neurons that secrete a molecule known as dopamine. The loss of dopamine’s effect on the basal ganglia leads to the signs and symptoms of Parkinsonism.

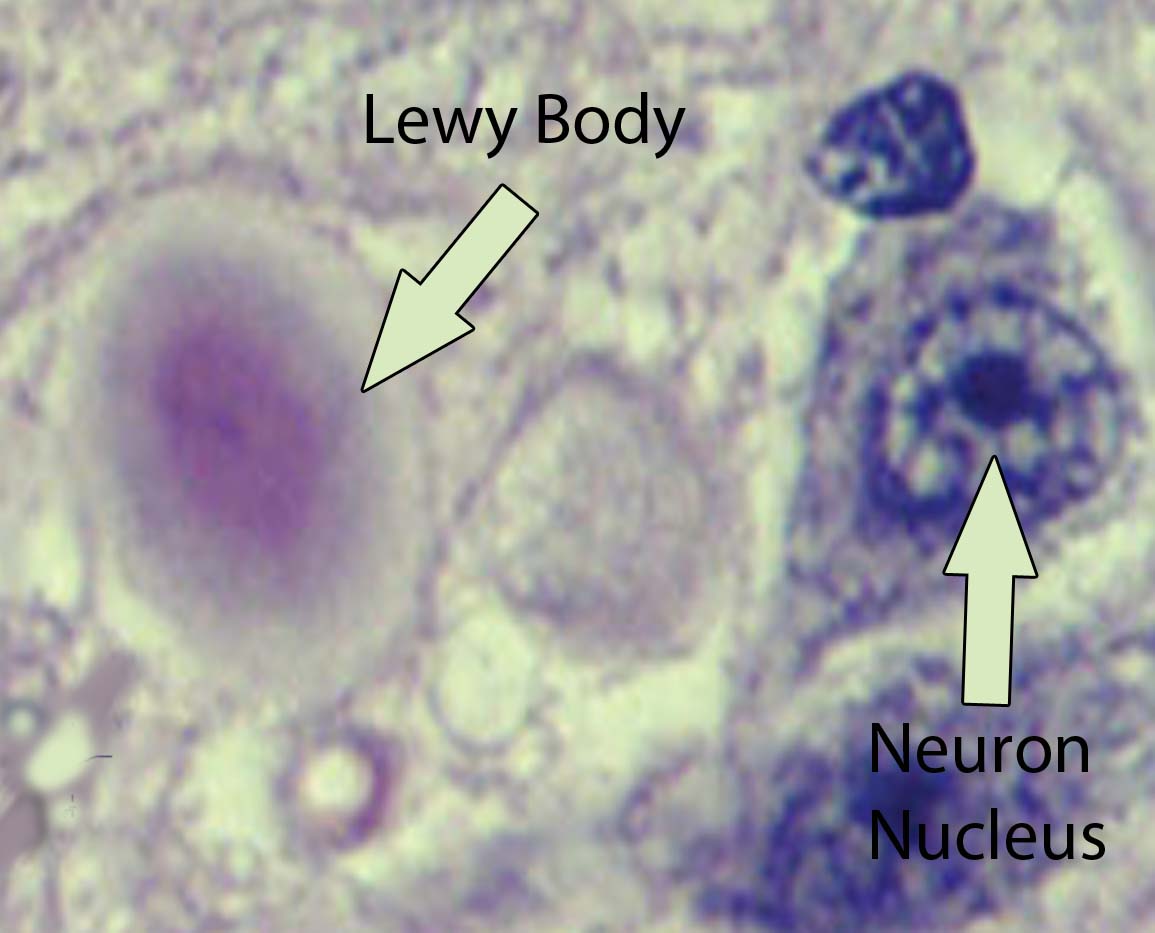

Visible abnormalities are also seen in the neurons of patients with Parkinson’s disease. These abnormalities are called Lewy bodies. They are collections of abnormal protein (specifically, a protein known as α-synuclein) that clump together to form a redish-pink cytoplasmic inclusion in the substantia nigra neurons.

For example, toxins such as carbon disulfide, manganese, and certain street drugs have been known to kill substantia nigra cells resulting in Parkinson’s.

Another toxin known as MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine, trying saying that four times fast!), which was produced accidentally by drug chemists trying to make a synthetic opiod, is extremely toxic to substantia nigra cells. It caused irreversible Parkinson’s disease in those who were unfortunate enough to ingest it!

Finally, the genetics of Parkinson’s disease are not well known. There appears to be multiple genetic causes of the disease. One such genetic mutation involves the gene for α-synuclein, the main component of Lewy bodies. Other genetic mutations may also play a role in Parkinson’s, but they appear to contribute to only a small percentage of cases.

Diagnosis

Parkinson’s disease is a clinical diagnosis. This means that there are currently no special laboratory tests that can reliably detect the disease. Instead, the disorder is diagnosed based on the clinical symptoms discussed below. A true pathological diagnosis can only be made at autopsy by looking at the neurons of the substantia nigra under a microscope.

Signs and Symptoms

Parkinson’s disease has a number of symptoms that commonly begin in the 6th and 7th decade’s of life. Most of these are related to difficulties with movement. The classic description of Parkinson’s involves several signs and symptoms: resting tremor (4-7 Hz frequency), postural instability, bradykinesia (slow movements), rigidity (of the cog-wheeling type), and masked facies.

In addition, late in the disease course other symptoms can become apparent. Roughly 10 to 15% of patients develop dementia. This is believed to be due to the development of Lewy bodies in the cerebral cortex. The dementia of Parkinson’s disease is likely on a continuum with another form of dementia known as Lewy body dementia.

This YouTube video illustrates the common signs and symptoms seen in Parkinson’s disease:

Treatment

The mainstay of treatment for Parkinson’s disease is replacing or augmenting dopamine levels in the brain. A molecule known as levodopa (L-dopa), which is a precursor of dopamine is commonly used. The reason L-dopa is given instead of dopamine is because it crosses the blood brain barrier more readily.

Once inside the brain, L-dopa is converted to dopamine by neuronal enzymes. Sinemet® is a common formulation of L-dopa. It also contains a molecule known as carbidopa. Carbidopa inhibits the breakdown of L-dopa in the body so that more of it can reach the brain. L-dopa is most effective at improving tremor and bradykinesia.

Other medications are designed to mimic the actions of dopamine in the brain. These medications are known as dopamine agonists. They bind to dopamine receptors and cause the same types of cellular reactions that dopamine normally would. The two common dopamine agonists in use today are ropinirole and pramipexole.

(1) Levodopa/carbidopa

(2) MAO-B inhibitors

(3) COMT inhibitors

(4) Dopamine agonists

(5) Anticholinergics

(6) Glutamate antagonists

(7) Deep brain stimulation

One category of medications that does this is known as MAO-B inhibitors. MAO, or monoamine oxidase, is an enzyme that normally breaks down monoamines like dopamine. Therefore, inhibitors of this enzyme decrease the break down of dopamine allowing it to remain in the brain longer. Selegiline and rasagiline are example of MAO-B inhibitors.

Another class of medications that perform a similar function to the MAOIs are the COMT inhibitors. COMT (catechol-O-methyl transferase) is an enzyme that breaks down dopamine. Entacapone is a COMT inhibitor that may increase the amount of dopamine in brain tissue.

Medications that interfere with another neurotransmitter known as acetylcholine are also sometimes used. These anticholinergic medications, namely benztropine (Cogentin) and trihexylphenidyl (Artane), are most useful for tremor reduction. Since acetylcholine is present in many parts of the body, the anticholinergics tend to have many side effects (the mnemonic "dry as a bone (dry mouth), mad as a hatter (delirium), blind as a bat (pupil dilation), and hot as a hare (fever)" is commonly used for symptoms pertaining to anticholinergic medications).

Finally, medications that antagonize the neurotransmitter glutamate are less commonly used. Amantadine is the name of one medication in this category. It helps mostly with decreasing, or smoothing out, fluctuations in movement.

If medical therapy fails to control symptoms then surgical interventions may be used. In the past a procedure known as pallidotomy was used. This involved making a tiny incision in part of the basal ganglia. This procedure has been replaced by deep brain stimulation (DBS). During DBS surgery small electrodes are implanted in certain areas of the basal ganglia.

Overview

Parkinson’s disease is characterized by postural instability, resting tremor, slow movements, and rigidity. It’s caused by loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra of the brain. Why these neurons die is not entirely understood. Diagnosis is based on clinical signs and symptoms. Treatment is by replacing or augmenting dopamine in the brain.

Related Articles

References and Resources

- Bekris LM, Mata IF, Zabetian CP. The genetics of Parkinson disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2010 Dec;23(4):228-42. Epub 2010 Oct 11.

- Ferrer I, Martinez A, Blanco R, et al. Neuropathology of sporadic Parkinson disease before the appearance of parkinsonism: preclinical Parkinson disease. J Neural Transm. 2010 Sep 23.

- Baehr M, Frotscher M. Duus’ Topical Diagnosis in Neurology: Anatomy, Physiology, Signs, Symptoms

. Fourth Edition. Stuttgart: Thieme, 2005.

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease

. Seventh Edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2004.

- Bickley LS, Szilagyi PG. Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking

. Ninth Edition. New York: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2007.