Both the term “acoustic” and “neuroma” are incorrect ways of describing a tumor that arises from the 8th cranial nerve (vestibulocochlear nerve). An "acoustic neuroma" is a tumor that arises from Schwann cells that myelinate the peripheral portion of the nerve; this technically makes them “schwannomas”.

In addition, the tumor does not arise from the acoustic division of the 8th cranial nerve (ie: the portion of the nerve responsible for hearing), but instead arises most commonly from the vestibular division (ie: the balance portion of the nerve). Therefore, the appropriate medical term given to these tumors is a “vestibular schwannoma”.

These tumors are frequently caused by mutations in genes responsible for controlling cell cycle, cell morphogenesis, cell development, cell death, and cell adhesion. A well known cause of vestibular schwannomas occurs in patients with neurofibromatosis (NF) type II.

In this condition, which is responsible for about 5% of acoustic neuromas, a mutation in the NF gene on chromosome 22 causes an absent or dysfunctional protein product. This protein normally serves as a tumor suppressor; once mutated, it is no longer able to suppress tumor growth. The growth of various cells, including Schwann cells, becomes unchecked. The end result? A vestibular schwannoma.

When viewed under a pathology microscope, vestibular schwannomas are composed of different patterns of tissue. The first pattern is referred to as Antoni A; it consists of densely packed, elongated cells with nuclear free areas of cytoplasmic extensions referred to as "Verocay bodies". The second pattern is, you guessed it – Antoni B. This pattern has fewer cells and appears "looser" than the type A pattern.

These tumors are considered "benign", which means that they do not spread (metastasize) to other areas of the body. Overall, acoustic neuromas increase in size at the rate of roughly 1mm per year, but about 50% of tumors show no growth at all! Although they are not malignant tumors they can still cause symptoms.

Signs and Symptoms

Vestibular schwannomas cause local signs and symptoms. Since they arise from the 8th cranial nerve (vestibulocochlear nerve), which is responsible for hearing and balance, almost all patients present with some degree of hearing loss. In type II neurofibromatosis acoustic neuromas arising from both vestibulocochlear nerves may cause deafness. Some patients have tinnitus (ie: ear ringing), as well as a sense of vertigo.

Symptoms that are less common are a result of the tumor pressing on adjacent cranial nerves. Dysfunction of the 7th cranial nerve (facial nerve) can cause weakness of the facial muscles. If the tumor presses on the 5th cranial nerve (trigeminal nerve) it can cause face numbness; if it touches the 6th nerve (abducens nerve) diploplia (ie: double vision) may occur.

Finally, if the tumor continues to grow, it can cause compression of the brainstem. This can block the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leading to a condition called hydrocephalus. These patients often have headaches, nausea, and vomiting secondary to increased pressure within the skull.

Diagnosis and Classification

Audiometric analysis is important in order to document hearing loss and for monitoring treatment outcomes. The most useful test is a pure tone audiogram. Differences in hearing ability between the two ears is suspicious for an acoustic neuroma, but not specific.

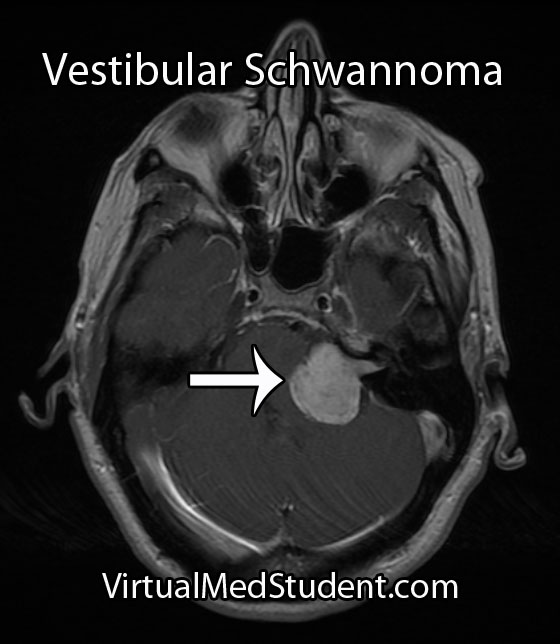

Although these tumors are commonly diagnosed from characteristic MRI findings, the definitive diagnosis is made when a pathologist looks at the tumor under a microscope.

A common classification system known as the Koos grading scale is frequently used. Grade 1 tumors involve only the internal auditory canal. Grade 2 tumors extend into the cerebellopontine angle, but do not encroach on the brainstem. A grade 3 tumor fills the entire cerebellopontine angle and a grade 4 tumor displaces the brainstem and adjacent cranial nerves.

Treatment

Treatment of these tumors depends on several factors, such as how large the tumor is, and whether or not the patient has symptoms from it (ie: hearing loss, face weakness, etc). If the tumor is small it can be followed with repeat MRI to monitor for enlargement. If the tumor grows, or begins to cause symptoms, then definitive treatment should be provided.

The two most commonly used treatment modalities are surgical resection and radiation. Surgery is most useful for very large tumors or when the patient is clinically deaf. Radiation comes in two flavors: single session stereotactic radiosurgery and fractionated radiotherapy.

Stereotactic radiosurgery is a single dose of radiation delivered directly to the tumor, typically with a dose of 12 to 13 Gy. The ability to preserve useful hearing with radiosurgery ranges from 32 to 71%. For tumors less than 3 cm in diameter, the ability of radiosurgery to halt the growth of the tumor has been shown to be between 92 and 100%.

Radiation can be harmful, especially when large doses are used in one session. Inadvertent injury to the facial nerve, acoustic nerve, trigeminal nerve, and brainstem are all possible adverse events. The use of fractionated radiotherapy has been tried to decrease these risks while still delivering large doses of radiation to the tumor.

Fractionated radiotherapy spreads the total radiation dose over multiple distinct sessions. For example, a total of 40 to 58 Gy can be delivered to the tumor in 2 Gy sessions over the course of several weeks. This is more radiation delivered to the tumor compared to single session radiosurgery (13 Gy), but it is delivered over a longer time frame, which helps mitigate the risk of damaging the adjacent cranial nerves and brainstem. Hearing preservation with fractionated radiotherapy has been shown to be superior to single-session radiosurgery.

Overview

A vestibular schwannoma is a benign tumor that arises from the vestibular portion of the 8th cranial nerve. It cause hearing loss and may cause compression of adjacent cranial nerves. It is diagnosed by clinical history, audiometric studies, and MRI. Treatment consists of surgical excision, radiation therapy, or both depending on the clinical situation.

More Brain Tumors…

- Ependymomas: Myxopapillary, Anaplastic, and Perivascular Pseudorosettes

- Glioblastoma: A Real Beast of a Tumor

- Colloid Cysts of the Third Ventricle

- Medulloblastoma: Sonic Hedgehog, Wingless, and Prognosis

References and Resources

- Ferrer M, Schulze A, Gonzalez S, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 2: molecular and clinical analyses in Argentine sporadic and familial cases. Neurosci Lett. 2010 Aug 9;480(1):49-54. Epub 2010 Jun 8.

- Cayé-Thomasen P, Borup R, Stangerup SE, et al. Deregulated genes in sporadic vestibular schwannomas. Otol Neurotol. 2010 Feb;31(2):256-66.

- Harner SG, Laws ER Jr. Clinical findings in patients with acoustic neurinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 1983 Nov;58(11):721-8.

- Bederson JB, von Ammon K, Wichmann WW, et al. Conservative treatment of patients with acoustic tumors. Neurosurgery. 1991 May;28(5):646-50; discussion 650-1.

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. Seventh Edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2004.

- Koos WT, Day JD, Matula C, et al. Neurotopographic considerations in the microsurgical treatment of small acoustic neurinomas. J Neurosurg. 1998 Mar;88(3):506-12.