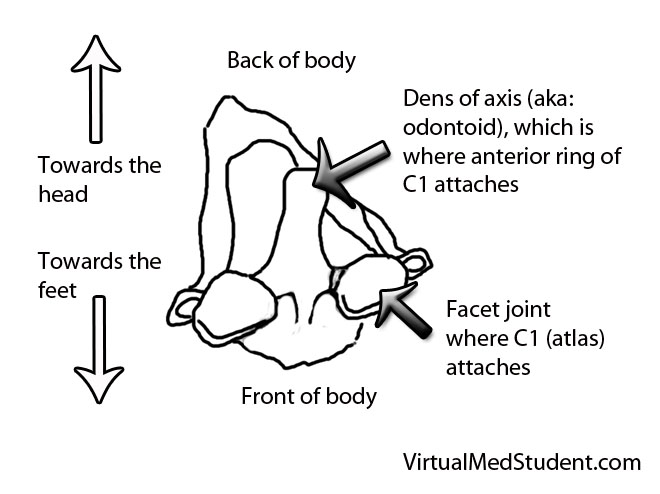

The atlas, or the first cervical vertebra (C1), is a ring shaped structure. It forms joints with the base of the skull above and the axis (ie: the second cervical vertebrae) below. It also has two foramen transversarium, which are holes that allow the passage of the vertebral arteries on either side of the spinal cord.

Fractures of the atlas occur most commonly with forceful axial loading of the head (ie: a downward force applied to the top of the head). Pressure on the top of the head causes the skull to push down on the atlas, which results in a break(s) of its ring-like structure. Specific fracture types such as a break in the front of the ring, the back of the ring, or one side of the ring versus the other, are dependent on additional force vectors at the time of loading (ie: flexion, extension, lateral bending, etc.).

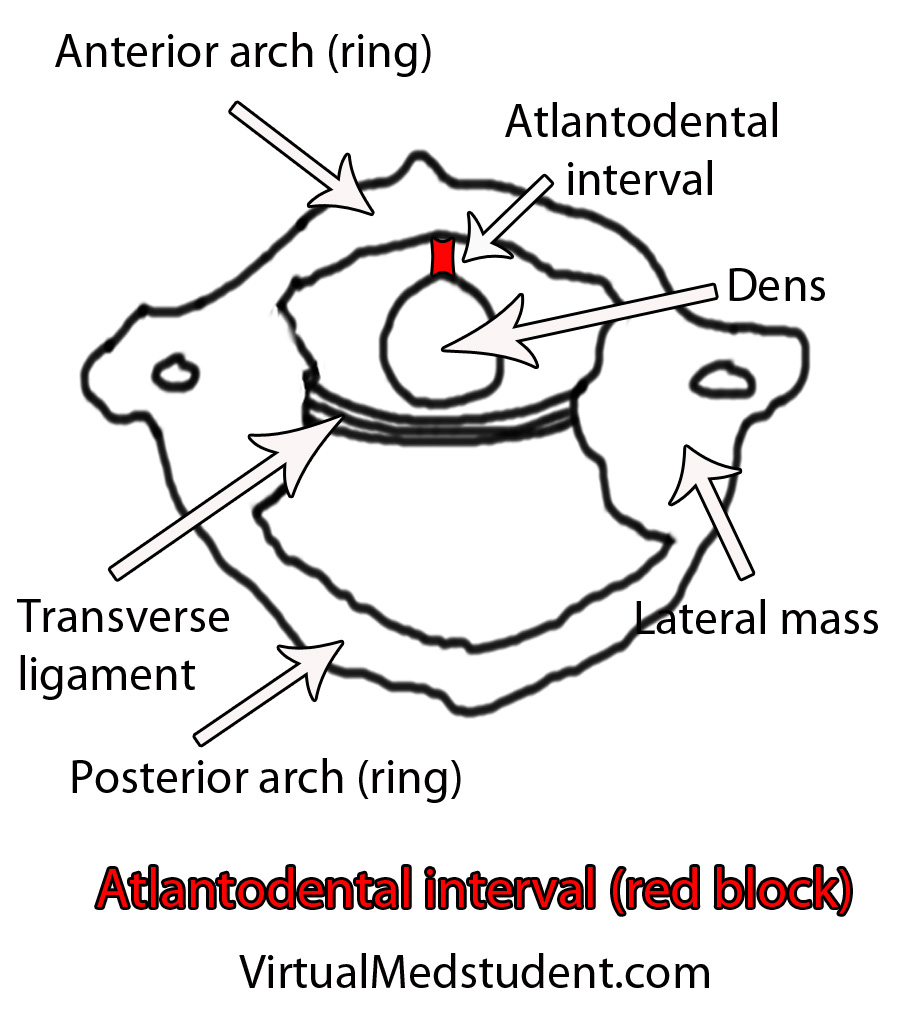

Fractures of the atlas must also include a discussion of biomechanical stability, which is usually determined by the integrity of the transverse ligament. The transverse ligament attaches the dens (odontoid) of the axis to the anterior ring of the atlas.

Fractures of the atlas with co-existent rupture of the transverse ligament lead to instability of the joint between C1 and C2. In other words, the ring of C1 may be able to move forward relative to the dens of C2. Transverse ligament injury is more common when axial loading is combined with extension of the head.

Not surprisingly, fractures of the atlas often co-exist with fractures of other cervical spine vertebrae. The most common combination is with a fracture of the axis, occurring in up to 40% of cases.

Signs and Symptoms

Patient’s with isolated atlas fractures usually have neck pain and muscle spasms. Frequently they have no injury to the spinal cord because the ring splays outwards as it fractures.

It is important to rule out injuries to the vertebral arteries, which run in bony holes (ie: foramen transversarium) on the sides of the atlas. When injured, the vertebral arteries can cause strokes in the brainstem and cerebellum, which can be life threatening.

Since the atlas is so close to the brainstem, patients may have co-existent injury to the lower cranial nerves. Specifically, injury to the 12th nerve can cause problems with tongue movements, injury to the 11th nerve can cause weakness with shoulder shrug and the ability to turn the head to the side, and injuries to the 9th and 10th cranial nerves can cause problems with swallowing and paralysis of the larynx leading to difficulty with speech.

Co-existent head and brain trauma, which can cause a constellation of different signs and symptoms depending on severity can also occcur.

Diagnosis

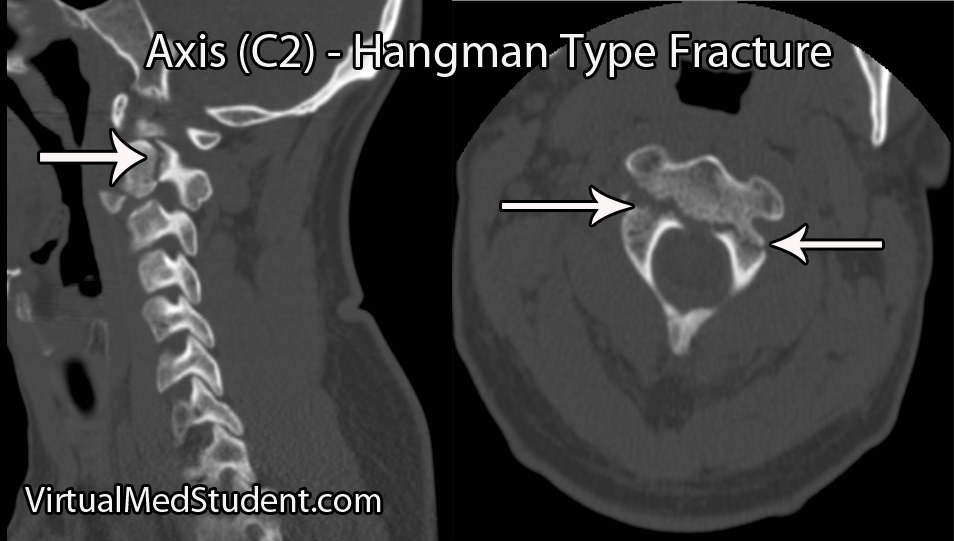

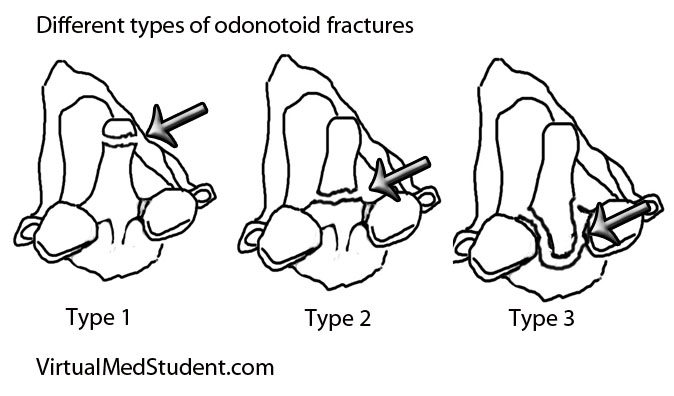

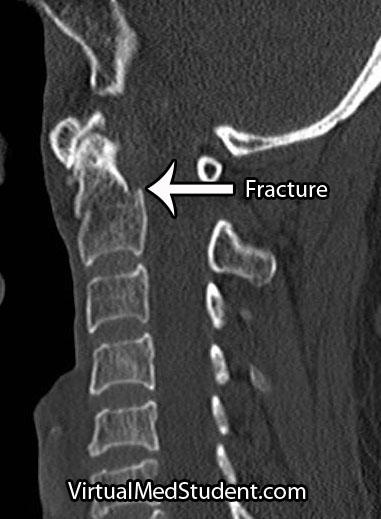

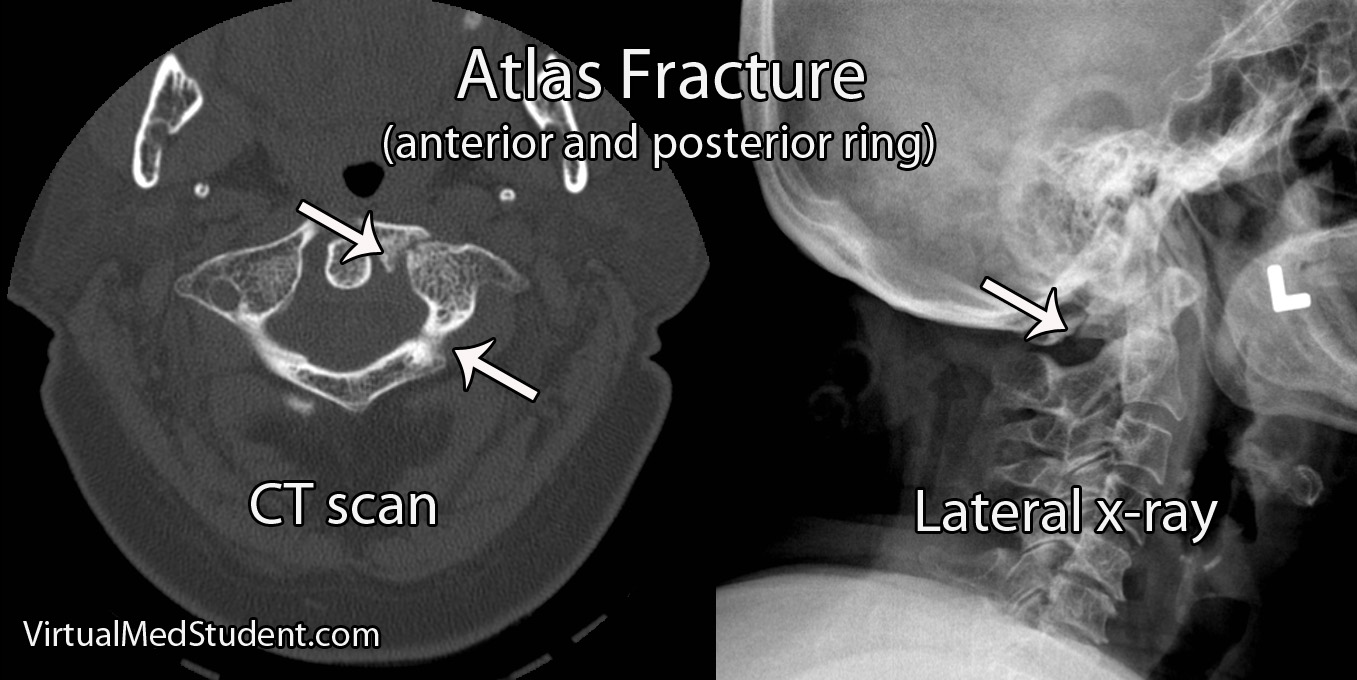

Diagnosis of an atlas fracture is made using x-rays, CT scans, and MRIs. X-rays should include anterior-posterior views, open mouth odontoid views, and lateral views of the cervical spine. If there is no evidence of neurological injury, flexion-extension x-rays may also be obtained to assess for stability of the C1-C2 joint.

The bony injury associated with atlas fractures is categorized according to the Jefferson or Landell and Van Peteghem classification systems. The Landells classification has three types, whereas the Jefferson classification has four types:

| Landell and Van Peteghem Classification | |

| Type 1 | Fracture of either the anterior or posterior ring, but not both (posterior ring fractures are most common type) |

| Type 2 | Fractures of both the anterior and posterior ring |

| Type 3 | Fracture of the lateral mass(es) |

| Jefferson Classification | |

| Type 1 | Fracture of the posterior ring only |

| Type 2 | Fracture of the anterior ring only |

| Type 3 | Fracture of the anterior and posterior rings on both sides; this is the classic "burst", or traditional “Jefferson” fracture |

| Type 4 | Fracture of the lateral mass(es) |

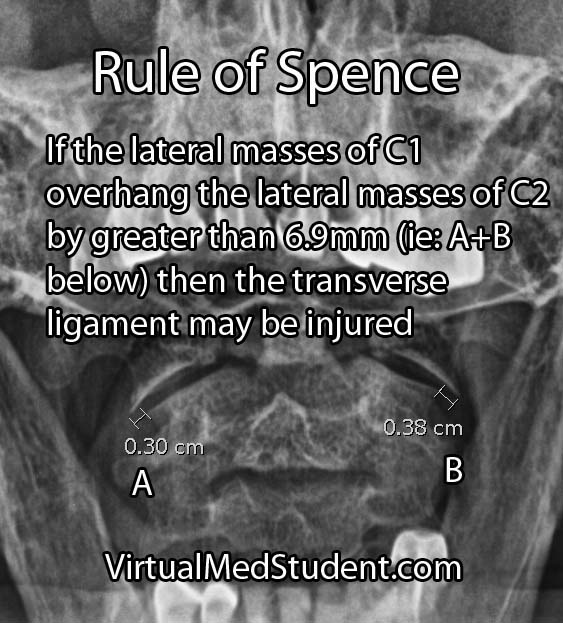

An important part of diagnosing atlas fractures involves assessing the integrity of the transverse ligament, which is best done using MRI. However, if an MRI cannot be performed then open mouth odontoid, flexion-extension x-rays, and CT scans can provide some information regarding transverse ligament injury.

The rule of Spence is one way of assessing the integrity of the transverse ligament on an open mouth odontoid x-ray. The rule states that if the right and left lateral masses of C1 overhang the lateral masses of C2 by greater than a total distance of 6.9mm than the likelihood of co-existent transverse ligament injury is high. The rule of Spence is not fool proof and should be supplemented with MRI and/or flexion-extension films whenever possible.

This interval is usually quite small, typically less than 3mm in adults and 5mm in children. If the interval is greater than this, then co-existent transverse ligament injury should be suspected.

Treatment

Treatment of isolated atlas fractures is usually with cervical immobilization. This may be with a halo or with a rigid cervical collar such as a cervical-occipital-mandibular-immobilizer (SOMI).

Atlas fractures that have co-existent transverse ligament rupture often require an operation to stablize the bones of the spine. This is usually in the form of fusing the atlas or occiput (back of the head) to the second cervical vertebrae.

If other injuries (ie: fractures of C2) are present and/or there is significant ligamentous injury then open surgical fusion of the bones may be necessary to re-create stability of the craniocervical junction.

Overview

Atlas fractures occur in response to vertical compression of the head on the upper cervical spine. Fractures of the anterior, posterior, or both rings of C1 may be present. Biomechanical stability is typically determined by assessing the integrity of the transverse ligament. Patients with isolated C1 fractures usually complain of neck pain, and rarely have injury to the spinal cord. Diagnosis is based on CT, x-ray, and MRI findings. Treatment is with rigid external immobilization or operative spinal fusion.

Related Articles

References and Resources

- White AA, Panjabi MM. Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine

. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1990.

- Junewick JJ, Chin MS, Meesa IR, et al. Ossification patterns of the atlas vertebra. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011 Nov;197(5):1229-34.

- Kakarla UK, Chang SW, Theodore N, Sonntag VK. Atlas fractures. Neurosurgery. 2010 Mar;66(3 Suppl):60-7. Review.

- Martin MD, Bruner HJ, Maiman DJ. Anatomic and biomechanical considerations of the craniovertebral junction. Neurosurgery. 2010 Mar;66(3 Suppl):2-6.

- Steinmetz MP, Mroz TE, Benzel EC. Craniovertebral junction: biomechanical considerations. Neurosurgery. 2010 Mar;66(3 Suppl):7-12.

- Yanni DS, Perin NI. Fixation of the axis. Neurosurgery. 2010 Mar;66(3 Suppl):147-52.