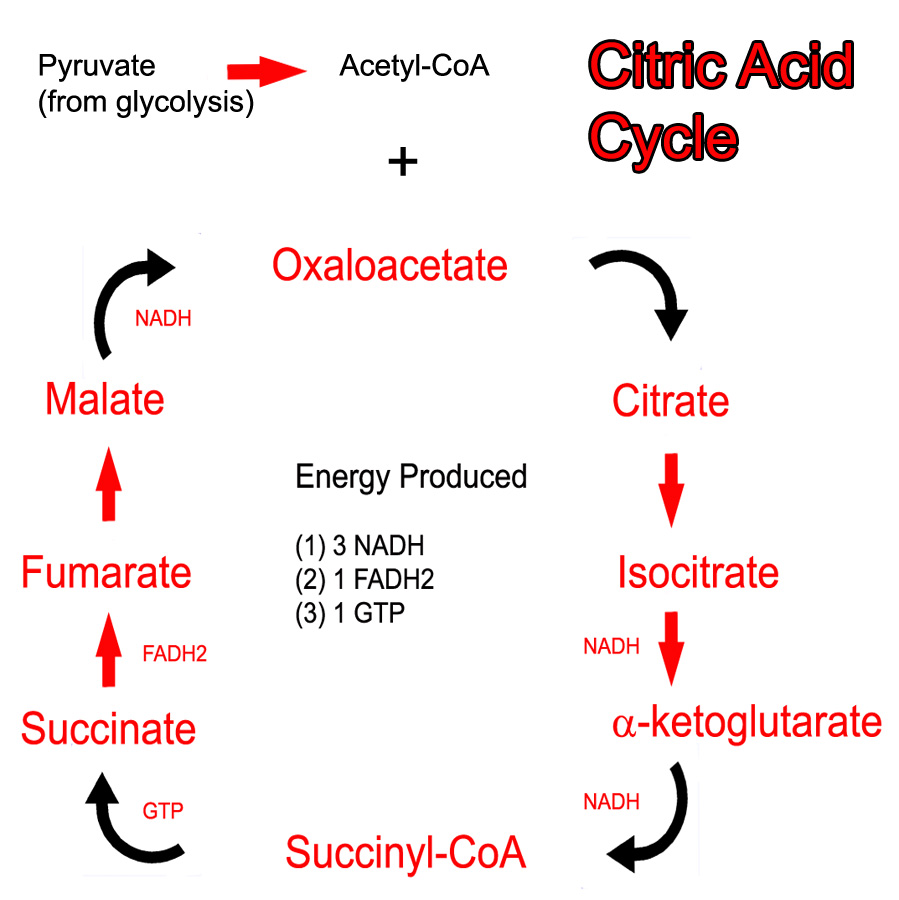

The main role of the citric acid cycle is to continue the oxidation (ie: energy "stripping") of acetyl-CoA. Acetyl-CoA can be obtained from the oxidation of pyruvate (the final molecule of glycolysis) or from the oxidation of long chain fatty acids.

The cycle begins when acetyl-CoA combines with oxaloacetate to form citrate. Several chemical reactions occur and citrate gets converted back to oxaloacetate (see cycle below). At this point, oxaloacetate re-combines with another acetyl-CoA to restart the cycle. Note that pyruvate and acetyl-CoA are NOT technically considered part of the cycle.

The Kreb’s cycle (aka: citric acid cycle) produces both energy and "waste". The waste are two molecules of carbon dioxide, which are formed from the two carbons present in the original acetyl-CoA molecule. The energy comes from removing electron pairs from the molecules in the cycle.

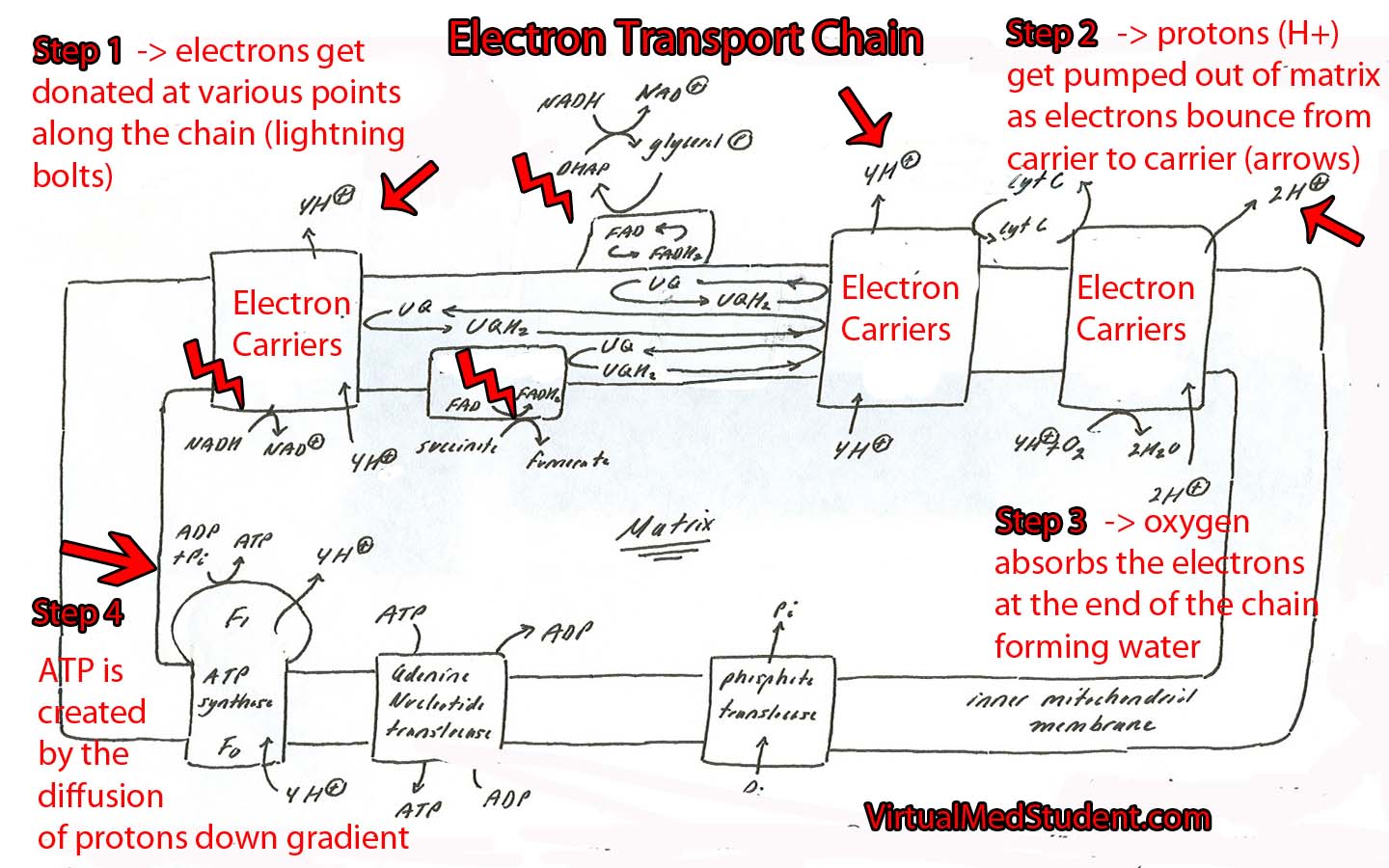

The cycle itself operates in the mitochondrial matrix. This is no mistake because the enzymes of the electron transport chain are located on the adjacent inner mitochondrial membrane; the NADH and FADH2 produced by the cycle do not have to travel far in order to donate their electron pairs.

Regulation

Two key enzymes control the citric acid cycle. The first is isocitrate dehydrogenase. This enzyme converts isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate. It is inhibited by ATP and NADH, and stimulated by ADP. If we think about it, this makes sense because if ATP and NADH are abundant (ie: the cell has adequate energy stores), then we want the cycle to slow down. ADP is the breakdown product of ATP and represents an energy depleted state. Thus, ADP stimulates the cycle so that more energy can be produced.

The second regulatory enzyme is α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase. This enzyme converts α-ketoglutarate to succinyl-CoA. It is inhibited by succinyl-CoA (an example of feedback inhibition), NADH, and ATP. The rationale behind this inhibition is similar to isocitrate dehydrogenase.

These two steps are also regulatory because they are highly exergonic. This means that they release lots of energy, so much so, that they are effectively irreversible reactions.

Overview

The main goal of the citric acid cycle is to produce energy by oxidizing acetyl-CoA. The energy produced comes in the form of NADH and FADH2. These molecules donate their electrons (energy) to the electron transport chain, which ultimately drives oxidative phosphorylation. This allows the formation of energy rich ATP, which can be used by the cell for numerous processes.

References and Resources

- Nelson DL, Cox MM. Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry. Fifth Edition. New York: Worth Publishers, 2008.

- Champe PC. Lippincott’s Illustrated Reviews: Biochemistry. Second Edition. Lippencott-Ravens Publishers, 1992.

- Le T, Bhushan V, Grimm L. First Aid for the USMLE Step 1. New York: McGraw Hill, 2009.