Diffuse axonal injury is a form of traumatic brain injury that occurs under conditions of rapid acceleration and deceleration of the head. This frequently occurs after high impact injuries such as motorcycle crashes or high speed car accidents.

Let’s discuss a few basic brain terms before we dive into why diffuse axonal injury happens. Brain tissue is composed of neurons and glia. The neurons communicate with one another through long extensions known as axons. You can think of an axon as the telephone wire that connects one phone to another. Axons compose the bulk of what is known as “white” matter in the brain; on the other hand, “gray” matter represents clumps of neurons.

Both gray and white matter have different densities associated with them. Because of this, rapid accelerations or decelerations of the head cause the gray matter to move at a greater relative velocity compared to the white matter. If these accelerations are severe enough stretch and shear injury occurs; the end result is that the “wires” get disconnected. This, in a nutshell, is diffuse axonal injury.

Signs and Symptoms

Depending on the severity of diffuse axonal injury patients may present with different signs and symptoms. In fact, diffuse axonal injury is frequently diagnosed when patients “fail” to wake up after a traumatic event despite adequate resuscitative treatment.

In its most severe form, diffuse axonal injury results in coma. Less severe injuries may cause long term cognitive issues and personality changes.

Diagnosis

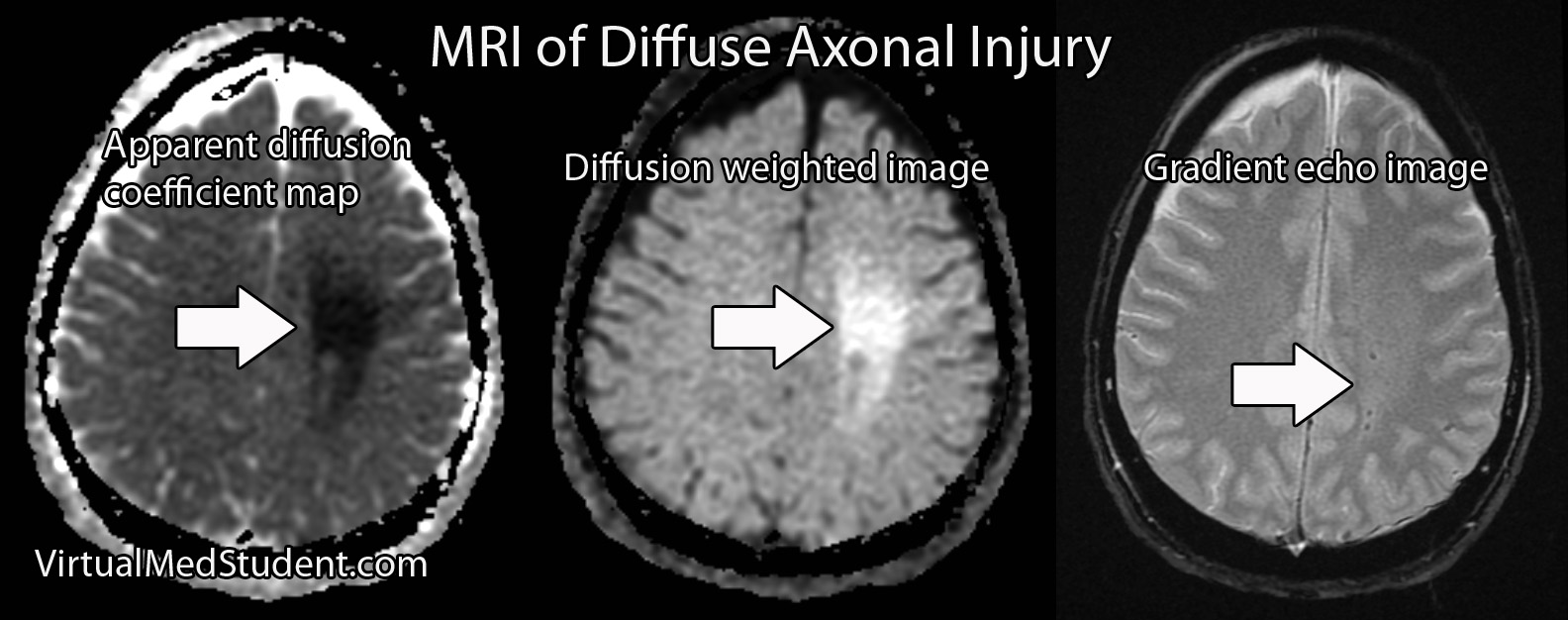

Diagnosis of diffuse axonal injury is made with an MRI scan. CT scans of the head are frequently ordered early to rule out other treatable causes for the decreased mental status often seen in patients with DAI (ie: epidural, subdural, and intraparenchymal hematomas).

The MRI will reveal restricted diffusion on diffusion weighted (DWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps of the brain. Gradient echo imaging (GRE) will often show small spots of low intensity consistent with shear/stretch injury.

Treatment

Unfortunately, there is no effective treatment for diffuse axonal injury. There is currently no way to “re-wire” the axons. All care for diffuse axonal injury at this point is supportive.

Overview

Diffuse axonal injury occurs after rapid changes in acceleration of the head. The axons, or “wires”, between neurons get stretched, sheared and, effectively disconnected. Coma is the common presenting sign of severe axonal injury. Diagnosis is made with MR imaging. Treatment is supportive since there is currently no way to re-wire the damaged connections.

Other Stuff You Might Want to Learn About

- Multiple Sclerosis: Scars in the Central Nervous System

- How to Systematically Interpret a Head CT: Blood Can Be Very Bad

- What do New Orleans and Canada Have in Common? Head CT Rules

References and Resources

- Hijaz TA, Cento EA, Walker MT. Imaging of head trauma. J Trauma. 2010 Dec;69(6):1610-8.

- Andriessen TM, Jacobs B, Vos PE. Clinical characteristics and pathophysiological mechanisms of focal and diffuse traumatic brain injury. J Cell Mol Med. 2010 Oct;14(10):2381-92.

- Meythaler JM, Peduzzi JD, Eleftheriou E. Current concepts: diffuse axonal injury-associated traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001 Oct;82(10):1461-71.

- Smith DH, Meaney DF, Shull WH. Diffuse axonal injury in head trauma. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2003 Jul-Aug;18(4):307-16.

- Osborn AG. Osborn’s Brain: Second Edition. Elselvier, 2017.