Pathology

What does the term atherosclerosis mean? If we break the term down into its components, "athero" is Greek for a gruel or paste, and sclerosis means hardening. This is precisely what is happening in the blood vessels of people with this disease; a paste-like material hardens to form a plaque. The specifics of how that paste-like material forms are much more complicated.

The paste-like material is composed of several different elements. The first, and perhaps most important element, is low density lipoprotein (ie: LDL). LDL, or the “bad cholesterol” as it is commonly referred, is a mixture of lipid (ie: fat and cholesterol) and protein. These molecules are highly atherogenic, which means they accelerate the plaque forming process.

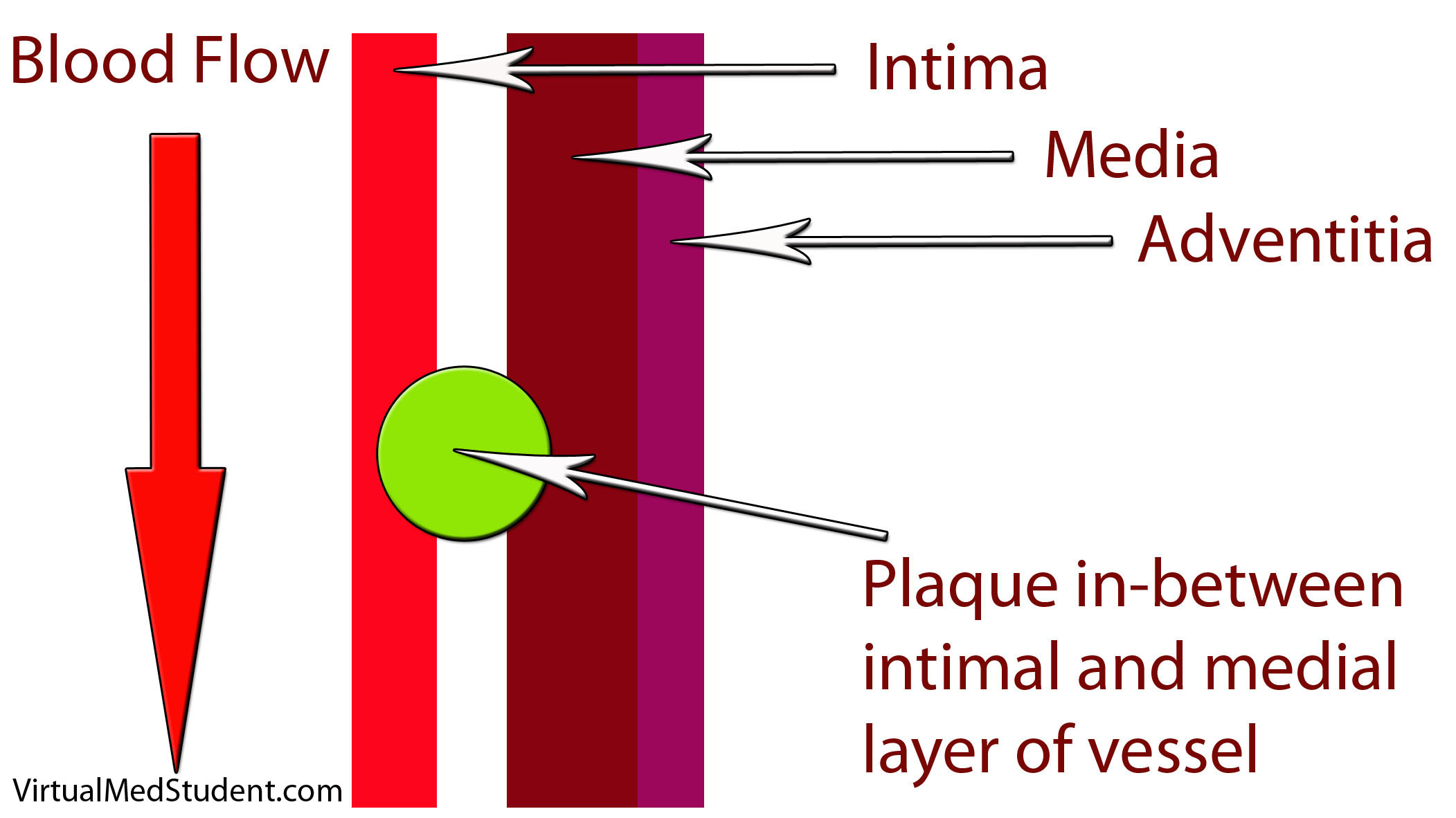

How does LDL lead to a plaque? The first step involves disruption of part of the blood vessel known as the intima. Blood vessels have three layers: intima, media, and adventitia. The intimal layer is the portion of the vessel directly in contact with blood flow. It is composed of endothelial cells, which have numerous important functions. The medial layer is smooth muscle that controls the diameter of the blood vessel; the adventitial layer is a connective tissue coating (ie: similar to the plastic coating surrounding an electrical wire) that anchors the vessel to adjacent structures in the body.

When the intimal layer is disrupted, LDL particles floating in the blood get trapped in the vessel wall. Once trapped, they start an inflammatory reaction. White blood cells (a key component of inflammation) known as macrophages are recruited to the vessel’s walland gobble up the intruding LDL particles. At this point the macrophages are known as “foam cells”. Foam cells get enmeshed in a web of scar and smooth muscle. All of this together becomes a "plaque".

Symptoms

The symptoms of atherosclerosis depend on how large the plaques are, and where they are located. The three common symptoms associated with atherosclerosis:

(1) Angina (chest pain) – read about acute coronary syndromes

(2) Transient ischemic attacks (TIA)

(3) Vascular claudication

Angina refers to chest pain that occurs with exercise (by exercise we refer to any activity above normal daily activity). The pain is a result of atherosclerotic plaque blocking the increased blood flow needed to supply the heart during strenuous activities. In essence, what is happening is that the heart is "starving" for oxygen, which results in chest pain. When the patient stops exercising the heart no longer needs as much oxygen; the amount of blood flow is again adequate, and the chest pain ceases. Angina is a harbinger of a potential heart attack.

Transient ischemic attacks are due to atherosclerosis in the blood vessels leading to the brain. The temporary decrease in blood flow to the brain caused by the blockages can result in stroke-like symptoms that resolve within twenty-four hours. TIAs are harbingers of potential strokes in the future.

If atherosclerosis develops in the vessels going to the lower extremities, vascular claudication occurs. Claudication refers to pain in the legs that worsens while walking (or running). Similar to angina, the pain is due to blocked blood flow to the legs secondary to the plaques. A condition known as "Leriche’s syndrome" occurs when there is decreased blood flow to not only the legs, but also the vessels leading to the penis. This causes not only lower extremity claudication, but also impotence.

The complications of atherosclerosis stem from the symptoms. They include myocardial infarction (eg: heart attack), of which angina is a warning sign; as well as cerebrovascular accidents (eg: strokes), of which transient ischemic attacks serve as a warning. Worsening disease in the lower extremities can lead to gangrenous limbs and the need for potential amputation.

(1) Myocardial infarction (eg: heart attack)

(2) Cerebrovascular accidents (eg: stroke)

(3) Worsening lower extremity disease -> amputations

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of atherosclerotic disease depends on the location of symptoms. If anginal chest pain is the main symptom several different studies can be done. One such study is the “stress test”. There are several different permutations of the stress test.

All of them include two components. The first is a method of "visualizing" the heart. This can be done by ECG, echocardiography (ie: ultrasound of the heart), or nuclear/radioactive scans. The second component involves "stressing" the heart. This is most commonly done by exercising on a treadmill, but medications like dobutamine can also be used if the patient cannot exercise for whatever reason.

| Stress Testing | |

| Methods for visualizing the heart’s function | – Electrocardiogram (ECG) |

| – Echocardiogram (echo) | |

| – Nuclear studies | |

| Methods for stressing the heart | – Exercise (ie: treadmill) |

| – Medications (ie: dobutamine, persantine, etc.) | |

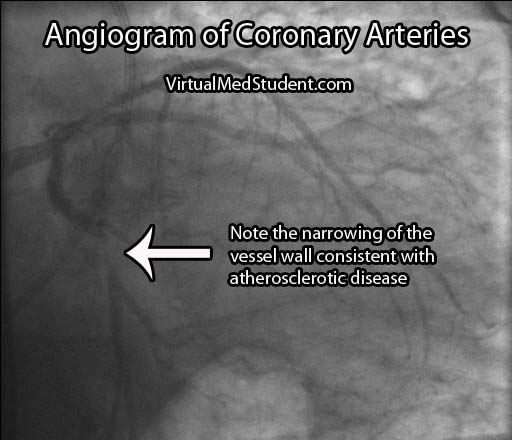

If the stress test is positive, or there is a high index of suspicion for atherosclerosis involving the coronary arteries, the next test performed is an angiogram. This involves injecting radio-opaque contrast material into the coronary arteries through a tiny catheter. The coronary arteries can then be visualized using x-rays. Areas where there is less contrast in the vessel indicate coronary atherosclerotic disease. The image below is an example of narrowing in the circumflex artery (indicated by the arrow).

If the involved areas are the carotid arteries, a test known as "carotid artery duplex scanning" can be done. This involves using ultrasound to detect the amount of blood flow present in the vessel(s). Decreased rates are often attributable to atherosclerotic disease.

Finally, if disease is thought to be present in the lower extremities, a test known as the arterial brachial-ankle index (ABI) is obtained. This test involves taking the blood pressure in the arm and the leg and comparing the results. Blood pressure should be about equal in the upper and lower extremities resulting in a brachial to ankle ratio of 1.0. However, if there is atherosclerotic diseases in the lower extremities the ABI decreases to less than 1.0.

| Location of suspected atherosclerotic disease: | Initial test performed: |

| – Coronary arteries | – Stress test |

| – Carotid arteries | – Duplex scanning |

| – Arteries of lower extremities | – Ankle-Brachial index (ABI) |

Occasionally cardiologists or vascular surgeons will recommend a more invasive procedure known as a "catheterization". In this procedure a small catheter is threaded from a blood vessel in the groin to the area of interest (ie: the heart, carotids, vessels of the lower extremities). From there radio-opaque dye is injected. A fancy X-ray machine can then pick up locations of significant plaque formation.

Treatment

Treatment is designed to prevent further plaque formation. Since LDL plays a crucial role in this process, it is a target of medical therapy, but in order to understand treatment we have to first understand how cholesterol gets into the body. Cholesterol is either (a) absorbed by the gut from your diet, or (b) produced naturally by your body through a series of biosynthetic reactions.

The first interventions for decreasing cholesterol in the body are, you guessed it, dietary modifications. By decreasing the amount of cholesterol in the diet it is possible to decrease the amount of cholesterol, either free or in the form of LDL, that is in the blood stream. There is also some evidence that replacing saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats (ie: α-linolenic acid, an ω-3 fatty acid) can decrease atherosclerotic plaque formation.

Unfortunately, diet and exercise are not always enough to decrease blood cholesterol levels to acceptable limits. Several medications have been developed, and as one could imagine, they target either cholesterol in the gut, or the biosynthetic machinery that produces cholesterol naturally.

There are several types of drugs that bind cholesterol in the gut to keep it from being absorbed. They are referred to as "bile acid binding medications" or "bile acid sequestrants". It is important to realize that bile acids, which are secreted by the liver and gallbladder, are rich in cholesterol.

Under normal circumstances they are reabsorbed by the gut and recycled back into the bile pathway. By inhibiting their re-absorption, cholesterol from the blood stream is recruited by the liver to replace the bile acids that were previously being recycled. The ultimate effect is that these drugs decrease the amount of cholesterol in the blood stream. There are three common medications in this category: colesevelam, cholestyramine, and colestipol.

Another medication, ezetimibe, directly binds to free cholesterol in the gut. As a result, less cholesterol is delivered to the liver. To compensate, the liver increases its ability to absorb LDL and other forms of cholesterol from the blood resulting in decreased plasma levels.

treatments:

(1) diet and

exercise

(2) bile acid

sequestrants

(3) statins

(4) niacin

(5) fibrates

A vitamin, niacin (ie: vitamin B3), can also lead to favorable effects on the lipid profile of the blood. It increases "good" cholesterol (ie: HDL). It is believed to perform these feats by increasing the activity of an enzyme, lipoprotein lipase, which normally breaks down VLDL particles (a precursor of LDL).

A final category of medications known as the "fibrates" decrease fat content in the blood. They do not necessarily affect LDL levels significantly, but they do decrease another atherosclerotic forming fat type known as triglycerides. The two common fibrates in use today are gemfibrozil and fenofibrate.

Overview

Atherosclerosis is due to LDL trapping in blood vessel walls. This trapping results in inflammation and the formation of a fibromuscular plaque. Symptoms include angina (ie: chest pain), lower extremity claudication, and transient ischemic attacks. Diagnosis is made by stress testing, carotid ultrasound, and ankle-brachial index; more invasive testing with groin catheters can be performed as well. Treatment is based on decreasing cholesterol absorption from the gut, or decreasing the bodies natural mechanism for creating cholesterol.

References and Resources

- Negi S, Nambi V. Coronary heart disease risk stratification: pitfalls and possibilities. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2010 Dec;6(4):26-32.

- Amarenco P, Lavallée PC, Labreuche J, et al. Prevalence of Coronary Atherosclerosis in Patients With Cerebral Infarction. Stroke. 2010 Nov 18. [Epub ahead of print].

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. Seventh Edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2004.

- Lilly LS, et al. Pathophysiology of Heart Disease: A Collaborative Project of Medical Students and Faculty. Fourth Edition. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2006.

- Flynn JA. Oxford American Handbook of Clinical Medicine (Oxford American Handbooks of Medicine). First Edition. Oxford University Press, 2007.