Background

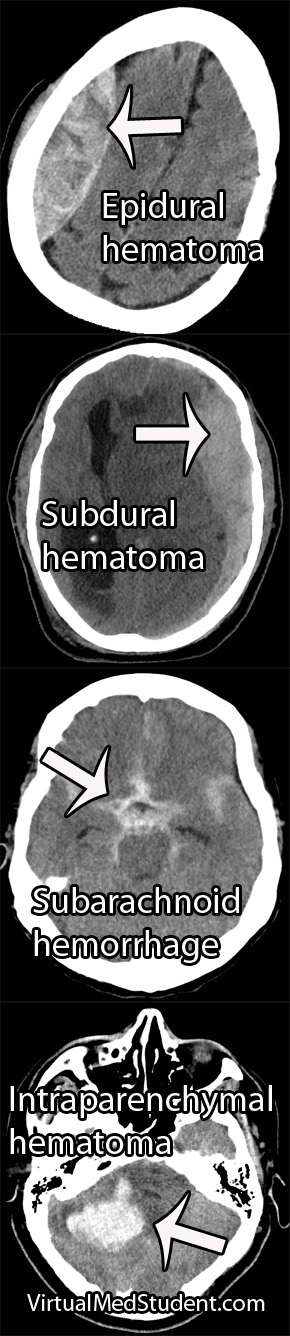

CT scans have become the sine-qua-non of assessing traumatic brain injury. CT scans of the head are fast and relatively inexpensive. In addition, they are able to pick up injuries that require emergent intervention.

CT scanners are so ubiquitous, at least in the United States, that it is easy to order a scan regardless of whether or not it is clinically indicated. The “scan everybody with a head bonk” mentality is dangerous for several reason. First, it exposes the patient to unnecessary radiation. Second, the term “relatively” inexpensive is exactly that, “relative”. CT scans are still costly by comparison, and every unnecessary scan only adds to the economic health care crisis.

So who should we scan? The literature on who to scan is based heavily on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). This scale divides patients with head trauma into three categories: mildly injured, moderately injured, or severely injured.

The Glasgow Coma Score is based on three behavioral components: eye opening, verbal performance, and motor responsiveness. Scores range from 3 to 15, with 15 being a "normal" score and 3 being completely comatose (or even dead!). Patients with a score of 8 or less are considered severely injured. Those with a score of 9 to 12 are considered moderately injured, and those with a score of 13 to 15 are considered mildly injured.

Patients with moderate to severe GCS scores should always be scanned. These people are at high risk for clinically important brain injury.

That brings us to the next question… What should we do with all the mild head bonks? The mildly injured patient usually looks good clinically (ie: a normal neurological examination), but may still harbor intracranial nastiness! So how do we determine which mild injuries to scan and which ones to send home?

The New Orleans Criteria

Scan if GCS 15 and

any of the following

are present…

– Headache

– Vomiting

– Age 60 or older

– Short term memory

problems

– Seizure

– Intoxicated

– Visible injury above

clavicles

The Canadian Head CT Rules

The second set of guidelines is known as the "Canadian Head CT Rules in Minor Head Injury". This set of guidelines states that any patient with a mild GCS score (ie: a 13, 14 or 15) are at high risk for neurosurgical intervention if the following factors are present: GCS score of less than 15 for longer than 2 hours after the injury, open or depressed skull fracture, signs of basilar skull fracture on physical examination, greater than two episodes of vomiting, and age greater than 65. In addition, patients at risk for brain injury (although not necessarily requiring surgical intervention) include those with amnesia longer than 30 minutes from the injury, or those involved in a dangerous mechanism of injury.

Comparing the Two Criteria

Scan if GCS 13, 14, or 15 and any

of the following are present…

– GCS < 15 at 2 hours

– Open/depressed skull fracture

– Vomiting > 2 times

– Signs of basilar skull fracture

– Age 65 or older

– Dangerous mechanism

– Antegrade amnesia > 30 minutes

Overview

Deciding who to scan after mild head injuries has been studied extensively. Currently, two common sets of criteria are used to decide who gets a CT scan. Both sets of criteria are sensitive in picking up clinically significant head injury, but the Canadian Head CT Rules are more specific than the New Orleans Criteria and may help further reduce unnecessary scanning.

References and Resources

- Washington CW, Grubb RL Jr. Are routine repeat imaging and intensive care unit admission necessary in mild traumatic brain injury? J Neurosurg. 2012 Mar;116(3):549-57.

- Stiell IG, Clement CM, Rowe BH, et al. Comparison of the Canadian CT Head Rule and the New Orleans Criteria in patients with minor head injury. JAMA. 2005 Sep 28;294(12):1511-8.

- Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974 Jul 13;2(7872):81-4. This is the original GCS paper.

- Bouida W, Marghli S, Souissi S, et al. Prediction value of the Canadian CT head rule and the New Orleans criteria for positive head CT scan and acute neurosurgical procedures in minor head trauma: a multicenter external validation study. Ann Emerg Med. 2013 May;61(5):521-7.