The Monro-Kellie doctrine states that three things exist within the fixed dimensions of the skull: blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and brain. An increase in any one component must necessarily lead to a decrease in one (or both) of the other components, otherwise intracranial pressure will increase.

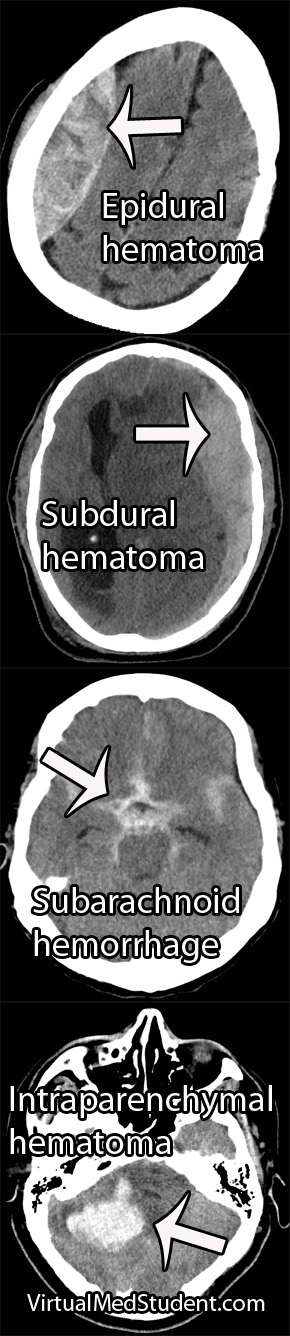

Increases in one of the three components can take many different shapes and sizes. For example, abnormal bleeding within the cranium such as in epidural and subdural hematomas are common examples, which typically occur after traumatic events. Bleeding within the brain tissue itself – known as an intraparenchymal or intracerebral hematoma – can also occur, especially in patients with untreated high blood pressure. Brain tumors of any type effectively increase the amount of brain tissue. And last, but not least, the cerebrospinal fluid can back up in a condition known as hydrocephalus.

Regardless of the cause, the end result is an abnormal increase in either blood, brain, or cerebrospinal fluid within the confines of the skull.

So what’s the big deal? If the abnormality becomes large enough, the pressure within the skull can increase rapidly. Eventually the pressure can become so great that the brain gets squished, and will pop over rigid boundaries and out the small holes within the skull.

This is known as “herniating” the brain tissue. It can occur in numerous places depending on where the pressure is greatest. However, the most important herniation clinically occurs at the base of the skull where a hole known as the foramen magnum exists.

When the brain herniates here it really pisses off a vital structure known as the brainstem. The brainstem is responsible for all the stuff we don’t consciously think about (heart rate, breathing, etc.), which ultimately keeps us alive. When herniation of the brainstem through the foramen magnum occurs it stretches all the “wires” that allow our brainstem to function properly. If severe enough, all those autopilot functions (ie: breathing, beating of the heart, etc.) stop working and brain death occurs.

Overview

The skull contains three components within it: blood, brain, and cerebrospinal fluid. An abnormal increase in any one of these components causes an increase in pressure, which if severe enough, can cause herniation of brain tissue out of the skull. This can lead to coma and brain death.

References and Resources

- Mokri B. The Monro-Kellie hypothesis: applications in CSF volume depletion. Neurology 56 (12): 1746–8. PMID 11425944.

- Frontera JA. Decision Making in Neurocritical Care

. First Edition. New York: Thieme, 2009.

- Greenberg MS. Handbook of Neurosurgery

. Sixth Edition. New York: Thieme, 2006. Chapter 25.

- Cushing H. The third circulation in studies in intracranial physiology and surgery. London: Oxford University Press, 1926: 1–51.

- Baehr M, Frotscher M. Duus’ Topical Diagnosis in Neurology: Anatomy, Physiology, Signs, Symptoms

. Fourth Edition. Stuttgart: Thieme, 2005.