A respiratory acidosis occurs when a person hypoventilates (ie: breathes too slow or too shallow). The result is an increase in PaCO2 (ie: the amount of CO2 dissolved in blood). The increase in plasma CO2 causes the blood to become acidic, which is manifest by a drop in the bodies’ pH. The reason blood becomes more acidic under these conditions is based on Le Chatelier’s principle. To understand this principle better let’s look at the equation that governs CO2 and HCO3– formation:

HCO3– + H+ <—> H2CO3 <—> CO2(g) + H2O

You’ll notice that CO2 (on the right most part of the equation) is what is exhaled via the lungs. When a patient is hypoventilating there is more CO2 than normal in the blood stream. The body compensates by turning this CO2 into HCO3– and H+. The resulting increase in H+ causes the acidosis (decrease in pH).

Causes

What causes someone to hypoventilate? There are many causes! All of them relate to a decreased ability of the patient to breath at a rate sufficient to remove carbon dioxide from the blood stream.

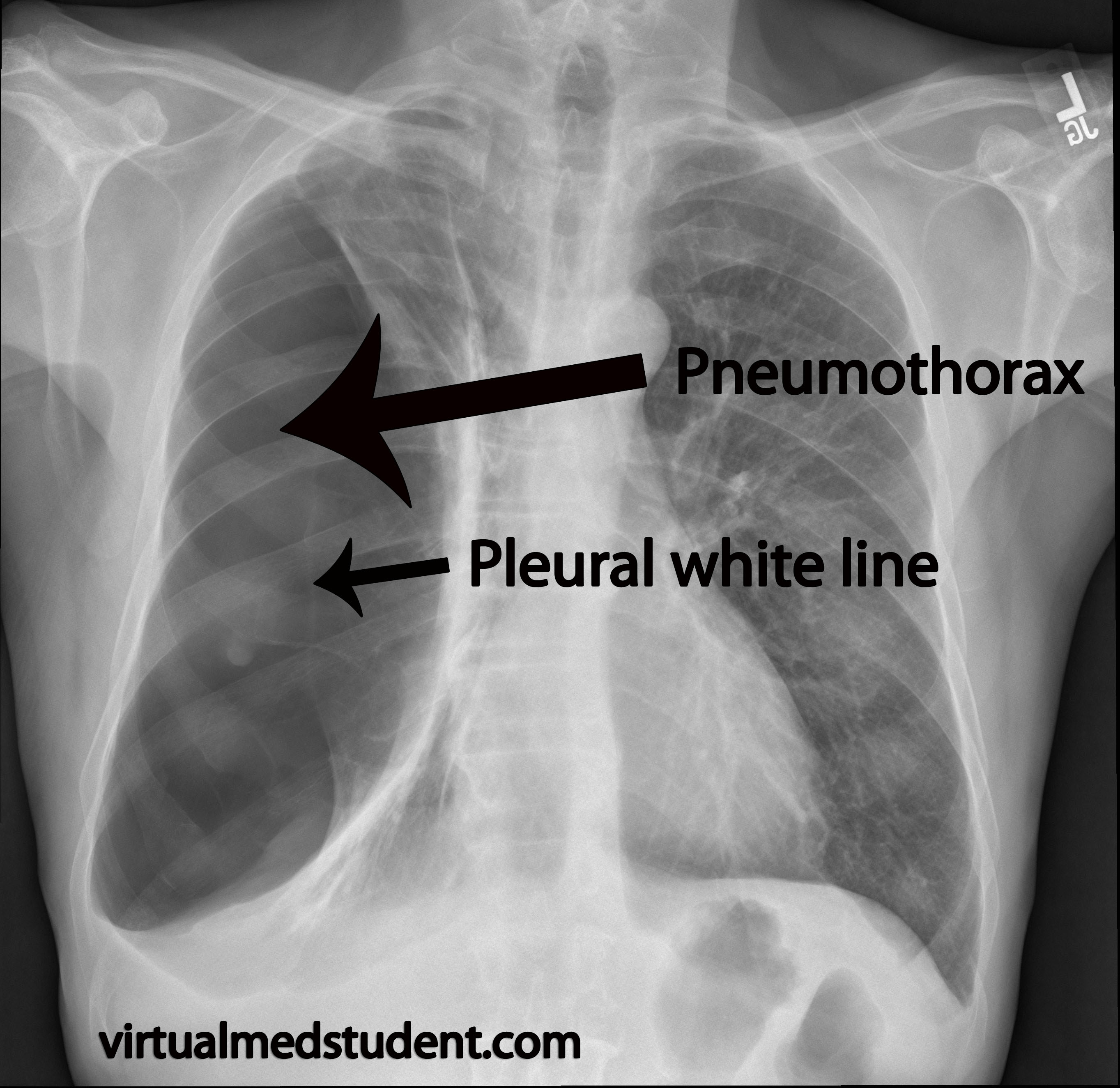

Medications that slow respiratory rate (ie: morphine and other pain medications) are notorious culprits. Poor pulmonary mechanics from obesity or neuromuscular disease (ie: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) can also cause decreased respiratory rates. Lung and chest wall diseases are also common causes of respiratory acidosis and include pneumonia, pneumothorax, and decreased respiratory rate secondary to pain from rib fractures.

When assessing someone who has a respiratory acidosis ask this question first: what is causing the patient to have a decreased respiratory rate? Look for signs of external chest wall trauma, pneumonia, etc. Look through the medication record (how much pain medication have they gotten?) to get an idea of what medications could be causing their decreased ventilatory drive.

In general, the most common causes of hypoventilation are:

- Medicines (especially pain medications)

- Airway obstruction

- Central nervous system disease (ie: diaphragmatic paralysis from cervical spinal cord trauma)

- Chest wall problems (pneumo/hemothorax, flail chest, broken ribs, etc.)

- Nerve and muscle diseases

- Lung diseases (ie: pneumonia, restrictive lung diseases, etc.)

Acute Versus Chronic and Kidney Compensation

A respiratory acidosis can be either acute or chronic. The difference depends on how much the kidney compensates for the change in pH. How exactly does the kidney compensate? It decreases its secretion of HCO3– (aka: bicarbonate ion) into the urine. This helps offset the acidosis, and brings the bodies pH back towards normal limits.

How do we determine if the kidney is acutely or chronically compensating? We measure the bicarbonate level (one of the results in a "chemistry panel"). The kidney is acutely compensating if the HCO3– level is increased 1 to 2 mmol/L per every 10 mmHg increase in the PaCO2 level (normal PaCO2 level is 40 mmHg). The kidney is chronically compensating if the HCO3– level is increased 3 to 4 mmol/L per every 10 mmHg increase in PaCO2.

For example, if a patient’s PaCO2 on blood gas analysis is found to be 60 mmHg (a normal level is 40) we would say there is a 20 mmHg increase present (ie: the patient is unable to eliminate 20 mmHg of excess CO2 from the blood stream via the lungs). If the HCO3– (determined by a chemistry panel) is at 27 (for argument sake we’ll say a normal bicarbonate level is 23) then that represents a 4 mmol increase in the bicarbonate level for the 20 mmHg increase in CO2, or approximately 2 mmol increase in bicarb per 10 mmHg increase in CO2. This would mean the patient’s kidney is acutely compensating for the respiratory acidosis.

| Bicarbonate Level (HCO3–) | |

|---|---|

| Acute Kidney Compensation | Increased by 1-2 mmol/L for every 10 mmHg increase in the PaCO2 |

| Chronic Kidney Compensation | Increased by 3-4 mmol/L for every 10 mmHg increase in the PaCO2 |

Why is it important to determine if acute or chronic kidney compensation is occurring? For starters, it gives the clinician a better idea of what may be causing the respiratory acidosis.

If the kidney is acutely compensating we know that the problem is new. The patient is likely having an acute issue (ie: trauma to the chest that caused multiple rib fractures). If the compensation is chronic then we know that the patient has been breathing at a slower than normal rate for a prolonged period of time. This may be seen in long standing neuromuscular diseases that cause poor pulmonary mechanics, obesity, etc.

Treatment

Treatment is straightforward: eliminate the underlying cause! If the patient received too much morphine give some naloxone to wake them up. Sometimes patients cannot maintain an adequate respiratory rate on their own, and mechanical ventilation is required. Once the patient is adequately ventilated the respiratory acidosis should resolve.

Overview

A respiratory acidosis occurs when a patient is unable to remove CO2 from the bloodstream secondary to a decreased respiratory rate (ie: hypoventilation). There are numerous causes including neuromuscular diseases, pain medication, and chest trauma. The kidney can acutely or chronically compensate for a respiratory acidosis depending on how long it has been present. Treatment is to fix the underlying cause.

You Are Just Getting Started… Learn Some More!

- Respiratory alkalosis: PaCO2 and Rapid Breathing

- Pneumothorax: Visceral and Parietal Pleura and a Little Air In-Between

References and Resources

- Lynes D. An introduction to blood gas analysis. Nurs Times. 2003 Mar 18-24;99(11):54-5.

- Ayers P, Warrington L. Diagnosis and treatment of simple acid-base disorders. Nutr Clin Pract. 2008 Apr-May;23(2):122-7.

- McCurdy DK. Mixed metabolic and respiratory acid-base disturbances: diagnosis and treatment. Chest. 1972 Aug;62(2):Suppl:35S-44S.

- O’Croinin D, Ni Chonghaile M, Higgins B, et al. Bench-to-bedside review: Permissive hypercapnia. Crit Care. 2005 Feb;9(1):51-9. Epub 2004 Aug 5.

- Curley G, Laffey JG, Kavanagh BP. Bench-to-bedside review: carbon dioxide. Crit Care. 2010;14(2):220. Epub 2010 Apr 30.