This article will discuss the basics of pregnancy. In order to understand the basics we have to understand two important obstetric terms: gravity and parity.

Gravity refers to the number of times a woman has been pregnant. Parity refers to how many times the woman has given birth to an infant older than 20 weeks gestational age, or weighing greater than 500 grams.

On a medical chart a woman’s obstetric history is commonly written as “G x P y”. “G” refers to the gravity, or the number of times, “x”, a woman has been pregnant. The “P” stands for the parity, or the number of times, “y”, a woman has given birth to an infant older than 20 weeks gestation, or weighing greater than 500 grams. In other words the “y” equals the number of pregnancies that made it past 20 weeks gestation.

However, a woman’s obstetric history may also contain miscarriages, abortions, preterm births, and still births. In addition, some of her children may have died early in infancy. To account for these facts the “Gx Py” system is sometimes written as “G x P y, a, b, c, d”. The “a” refers to the number of term pregnancies; the "b" refers to the number of preterm pregnancies. The "c" refers to the number of abortions; abortions includes both spontaneous and induced, as well as ectopic pregnancies. And finally, the "d" refers to the number of living children the woman currently has.

So, as an example, a woman with two living children and one previous spontaneous abortion at twelve weeks gestation, who is currently pregnant for the third time would have an obstetric chart that reads "G 3 P 2, 2, 0, 1, 2."

Fetal Age nd Due Date

(1) Developmental age

(2) Gestational age

The developmental age is the age of the fetus measured from the time of fertilization. Since it is often difficult to determine exactly when fertilization occurred, a surrogate marker is used.

The surrogate marker is the gestational age. The gestational age is measured from the first day of the last menstrual period. Typically, the gestational age overestimates the developmental age by approximately two weeks.

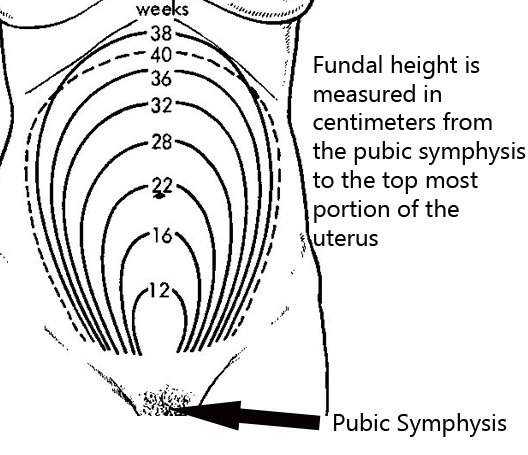

If the last menstrual period is not known there are other ways of determining the gestational age. One method is to use fundal height; fundal height is the location of the fundus (ie: the top most portion of the uterus) as felt by palpating the maternal abdomen. By 20 weeks of gestation the fundal height should be at the mother’s umbilicus (belly button). From there on, the height roughly correlates with gestational age (ie: at 28 weeks the fundal height is 28cm above the pubic symphysis).

The second method, albeit an even more imprecise one, is to use quickening. Quickening is the detection of fetal movements by the mother. It usually corresponds to a gestational age of 17 to 18 weeks. Ultrasound can also be used to determine the gestational age, and is the most reliable way, assuming the last menstrual period is not known.

In order to calculate the delivery date a simple mathematics trick known as Nagele’s rule is used. It states that the estimated delivery date is determined by adding nine months plus seven days to the first day of the last menstrual period.

Naegele’s rule -> Last menstrual period + 9 months + 7 days = expected due date

Pregnancy Tests

How exactly do you determine if someone is pregnant? The most common way is to use a urine pregnancy test. These tests detect a molecule known as beta-HCG (ie: beta human chorionic gonadotropin). Beta-HCG is a molecule secreted by the placenta. Its level doubles roughly ever 48 hours during the first few days of pregnancy. It peaks at about 10 weeks of gestation. Urine tests tend to have a high false negative rate. This means that they miss pregnancies, especially if the pregnancy has just begun.

A more sensitive test is the serum (ie: blood) pregnancy test. This test measures exactly the same molecule, beta-HCG, but it does so from a blood, rather than a urine sample. This test can pick up pregnancies earlier than a urine test can.

Related Articles

References and Resources

- Wagner B, Meirowitz N, Shah J, et al. Comprehensive Perinatal Safety Initiative to Reduce Adverse Obstetric Events. J Healthc Qual. 2011 Mar 1.

- Whitworth M, Bricker L, Neilson JP, et al. Ultrasound for fetal assessment in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Apr 14;(4):CD007058.

- Beckmann CRB, Ling FW, Smith RP, et al. Obstetrics and Gynecology

. Fifth Edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2006.

- Bickley LS, Szilagyi PG. Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking

. Ninth Edition. New York: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2007.