Crohn’s disease is one of the inflammatory bowel diseases. Its pathology is related to transmural (ie: full wall thickness) inflammation of the bowel wall. Why this inflammation occurs is not particularly well understood.

Genetics appears to play an important role. Specific human leukocyte antigen genes are associated with Crohn’s (DR1/DQ5). In addition, there is a gene known as IBD1 that increases the risk of Crohn’s disease. The IBD1 gene encodes a protein called NOD2. This protein normally helps people “contain” bacteria in the gut. In some patients with Crohn’s disease the protein is mutated and does not function properly.

The immune system also plays an important role. For reasons that are actively being researched patients with inflammatory bowel disease may attack bacteria in the intestine that would otherwise be left alone. This leads to inflammation of the gut wall. Why dysregulation of the immune system occurs is not well understood, but many different types of immune cells are involved including T-cells, neutrophils, and macrophages.

The inflammation in Crohn’s disease can affect almost any location in the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the colon. The terminal ileum and proximal colon are the most common sites affected. Roughly 40% of cases involve the small bowel only. Pathological specimens resected from patients with the disease show noncaseating granulomas, aggregates of lymphocytes (ie: a type of white blood cell) in the bowel wall, and extension of fat along the serosal surface.

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms usually start between the ages of 15 and 40, with a second smaller peak starting between 50 and 80. Men and women are affected equally.

Diarrhea, abdominal pain, and weight loss that are chronic, or occur repeatedly are concerning for Crohn’s. Blood in the stool is not always seen, but may be present. Since any portion of the gastrointestinal tract can be involved, some patients have oral manifestations such as aphthous ulcers (“canker sores”).

Complications can occur and include bowel wall perforation, abscess formation, and strictures (ie: narrowing) of the bowel’s diameter resulting in obstruction. Fistulas, which are abnormal connections between two unrelated organs/body parts can occur between the bowel and the skin (enterocutaneous), bowel and bladder (enterovesicular), bowel and vagina (enterovaginal), and between adjacent bowel segments (enteroenteric).

Non-intestinal manifestations are also common. They include an arthritis that migrates around the body and involves multiple joints. Uveitis is inflammation of the uvea of the eye, which can lead to a painful eye and vision problems. Ankylosing spondylitis and sacroiliitis are inflammatory conditions of the axial skeleton that can co-exist with Crohn’s. Erythema nodosum, which is inflammation of the fat cells under the skin commonly occurs around the shins in patient’s with Crohn’s. Finally, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), which is inflammation of the bile ducts, both inside and outside the liver, can also occur (PSC is more strongly associated with ulcerative colitis).

Patient’s with long standing Crohn’s disease are also at risk of developing colon cancer, although the risk is less than that seen in ulcerative colitis.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on the history provided by the patient and imaging studies. Imaging studies can be x-rays taken after contrast is given (barium). The x-rays may show a “string sign”. The string sign is a result of nodular outpouchings of the bowel wall (secondary to inflammation), alternating with normal areas.

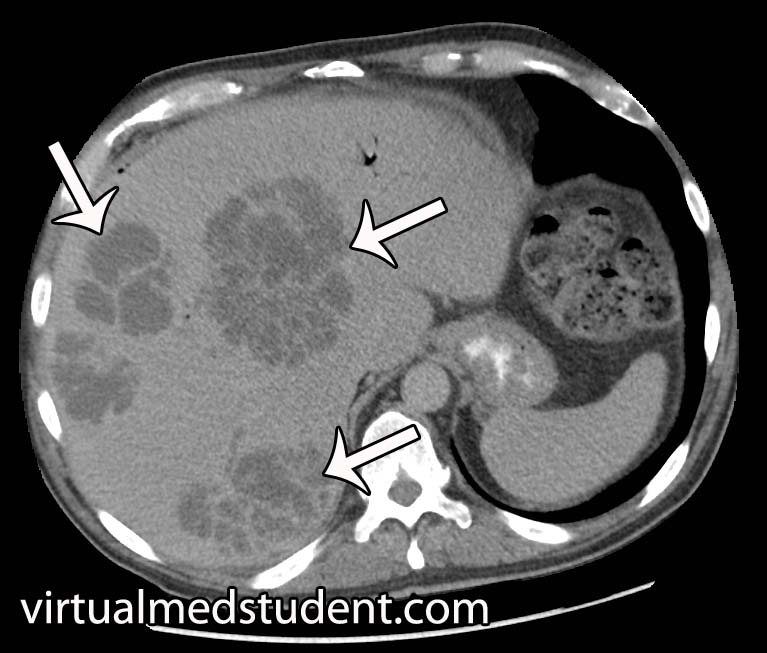

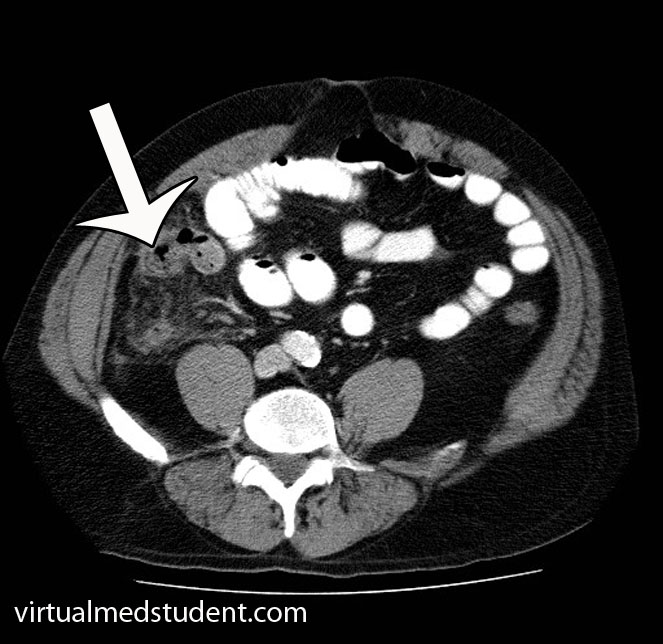

CT and MRI scans of the abdomen with contrast can show increased thickness of the bowel wall; they can also show abscess and fistulae formation, which are complications of the disease.

The "gold standard" for diagnosis is colonoscopy with biopsy of affected tissue. Skip lesions, in which areas of inflammation alternate with normal bowel, are highly suggestive of Crohn’s disease. The bowel wall will often appear “cobblestoned” and aphthous ulcers may also be present along the mucosal surface.

Treatment

Active Crohn’s disease is usually treated with one or more medications depending on the severity. Severe flairs of the disease are treated with steroids like prednisone.

Mild to moderate disease is often treated with one of the 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) derivatives. Sulfasalazine and mesalamine are two such derivatives. Unfortunately, 5-ASA medications do not appear to prevent relapses.

Some patients will not respond to prednisone or 5-ASA medications. For disease that does not respond to the above medications there are other options such as azathioprine and methotrexate.

Finally a class of medications known as “biologics” can be used. These medications dampen the immume response and therefore decrease the inflammation that occurs in autoimmune diseases. These include the anti-tumor necrosis factor medications known as infliximab and adalimumab. Vedolizumab (Entyvio®) blocks integrins on the surface of immune cells from binding to cells in the GI system. Ustekinumab (Stelara®) works on a molecule known as an interleukin, which is involved in inflammation. And last, but not least, risankizumab (Skyrizi®) also blocks a specific interleukin (number 23 to be exact), which decreases inflammation.

Overview

Crohn’s disease is characterized by inflammation of the entire bowel wall. It manifests with both gastrointestinal and extra-intestinal symptoms. It is diagnosed by history and imaging studies. Treatment is with immune dampening therapies like prednisone, 5-ASA derivatives, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate, and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors.

Other Stuff You May Want to Learn About

- Barrett’s Esophagus: Epithelial Metaplasia

- Appendicitis: A Vestigial Remnant to Belly Pain

- Cholelithiasis: Female, Fat, Fertile, and Forty

- Sir William Ogilvie and His Syndrome: Colonic Pseudo-Obstruction

References and Resources

- Gura Y, Bonen DK, Inohara N, et al. Frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Nature 2001 May 31;411(6837):603-6.

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. Tenth Edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2004.

- Akobeng AK, Gardener ES. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for maintenance of medically-induced remission in Crohn’s Disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Jan 25;(1):CD003715.