The heart is encased in a connective tissue capsule known as the pericardium. The pericardium contains two layers, known as the parietal and visceral pericardium. These layers are like two blankets enveloping the heart. The visceral pericardium sits adjacent to the heart muscle itself and the parietal pericardium sits on top of the visceral pericardium. Because of this arrangement there is a potential space between the two layers.

When fluid (ie: blood, pus, water, etc.) leaks into this space a pericardial effusion is present. Fluid can leak out quickly, in which case the effusion is said to be “acute”; or it can leak out gradually in which case it is said to be “chronic”.

Causes

There are numerous causes of pericardial effusion some of which are listed below:

- Infections

- Viral (including HIV, coxsackie, echo, adeno, ebstein-barr, and varicella viruses)

- Bacterial (including pneumococcus, neisseria meningitides, staphylococcus aureus)

- Tuberculosis

- Malignancies (cancers)

- Autoimmune conditions (including connective tissue disorders, vasculitis, and drug induced)

- Uremia (from renal failure)

- Cardiovascular (cardiac surgery, myocardial infarction, aortic dissection, congestive heart failure)

- Hypothyroidism

- Cirrhosis (liver problems)

- Idiopathic (unknown)

Please note that by no means is this list exhaustive, but these are the most common causes of effusions!

Signs and Symptoms

The classic symptom of pericardial effusion is chest pain that is better when the patient sits up and leans forward. However, numerous other symptoms including light headedness, shortness of breath, cough, and palpitations can occur.

Depending on how quickly the effusion develops, patients may spiral into a condition known as “tamponade”. When this occurs the effusion effectively “chokes” the heart muscle causing decreased contractile function. This causes decreased cardiac output and even multi-organ failure if left untreated!

The classic signs of tamponade are hypotension (ie: decreased blood pressure), muffled heart sounds, and increased jugular venous pressures (you can see the jugular veins engorged with blood). These three signs are known as “Beck’s triad”, which is generally a late finding of tamponade (ie: the patient is almost dead!).

Diagnosis

Treatment

For chronic effusions with no significant symptoms patients can be treated for the underlying condition causing the effusion. This will sometimes cure the effusion. However, in patients with acute presentations who have signs of cardiovascular instability (ie: low blood pressure, evidence of organ dysfunction from decreased blood flow, etc.) emergent removal of the fluid is performed. The quickest way to do this is to insert a needle under the xyphoid process and aspirate the fluid. In less acute situations, or in recurrent cases, surgical “windows” in the pericardial tissue can be created to allow the effusion to drain.

Overview

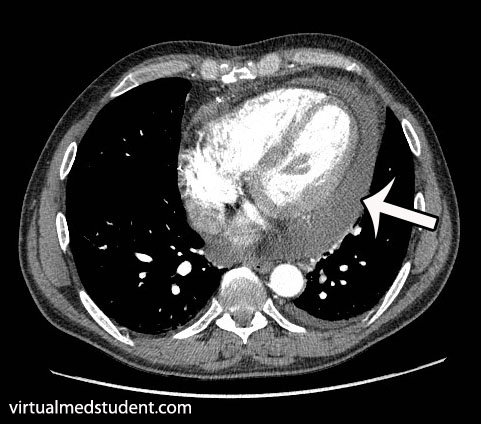

Pericardial effusions occur when fluid accumulates between the visceral and parietal pericardial layers surrounding the heart. There are numerous causes. Rapidly expanding effusions can cause cardiac tamponade and lead to cardiovascular collapse. Signs and symptoms include chest pain, shortness of breath, cough, distant heart sounds, and decreased blood pressure. Diagnosis is made by characteristic ECG, echocardiography, and CT scan findings.

References and Resources

- Imazio M, Brucato A, Mayosi BM, et al. Medical therapy of pericardial diseases: part II: Noninfectious pericarditis, pericardial effusion and constrictive pericarditis. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2010 Nov;11(11):785-94. Review.

- Khandaker MH, Espinosa RE, Nishimura RA, et al. Pericardial disease: diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010 Jun;85(6):572-93. Review.

- Spodick DH. Pericarditis, pericardial effusion, cardiac tamponade, and constriction. Crit Care Clin. 1989 Jul;5(3):455-76.

- Mookadam F, Jiamsripong P, Oh JK, et al. Spectrum of pericardial disease: part I. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2009 Sep;7(9):1149-57.

- Jiamsripong P, Mookadam F, Oh JK, et al. Spectrum of pericardial disease: part II. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2009 Sep;7(9):1159-69.

- Woo KM, Schneider JI. High-risk chief complaints I: chest pain–the big three. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2009 Nov;27(4):685-712, x.