The posterior longitudinal ligament is a long ligament that runs from the base of the skull to the sacrum. It provides a significant amount of mechanical integrity to the spinal column. The ligament runs down the back of the vertebral bodies just in front of the spinal cord itself.

In some individuals this ligament becomes ossified, which means that it takes on a bone like quality. As a result, its overall size and hardness increase. Given the ligament’s location adjacent to the spinal cord, any increase in the girth or flexibility of the ligament can cause injury to the cord.

Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament can occur at multiple spots along the spinal column. The most common spot is in the cervical spine (usually C2 to C6), but ossification can also occur in the thoracic (usually T4 to T7) and lumbar spine as well.

Exactly why the longitudinal ligament ossifies in some people is unknown. Current thinking is that a combination of genetic and lifestyle factors play a role in its pathology. For example, family studies have shown increased rates of OPLL in first degree relatives of people known to have the disorder. OPLL is also more common in people of Japanese and Korean descent.

Both familial and racial linkage usually indicate a genetic component to the disease. In fact, patients with OPLL have higher rates of dysfunctional collagen gene regulation (specifically, type XI and VI collagens). Linkage to specific human leukocyte antigen haplotypes on chromosome 6 have also been implemented.

Lifestyle factors such as diet have also been shown to increase risk. Patient’s who are diabetic or pre-diabetic have higher rates of OPLL compared to the rest of the population. High protein diets seems to decrease the risk, whereas high salt diets seem to increase risk.

Overall, the reasons why the posterior longitudinal ligament ossifies in some people, but not others remains an area of ongoing debate and research.

Signs and Symptoms

When an ossified posterior longitudinal ligament pushes on the spinal cord it causes numerous signs and symptoms. The constellation of clinical findings seen in patient’s with symptomatic ossified posterior longitudinal ligaments is known as myelopathy.

Myelopathic patients present with a combination of weakness, clumsiness (ie: decreased ability to hold objects), bowel or bladder dysfunction, spasticity – which is manifested as increased reflexes, as well as changes in sensation (ie: numbness, tingling, etc.).

Diagnosis and Classification

Diagnosis of an ossified posterior longitudinal ligament is usually made when a patient presents with myelopathic features, or after neurological injury from a traumatic event.

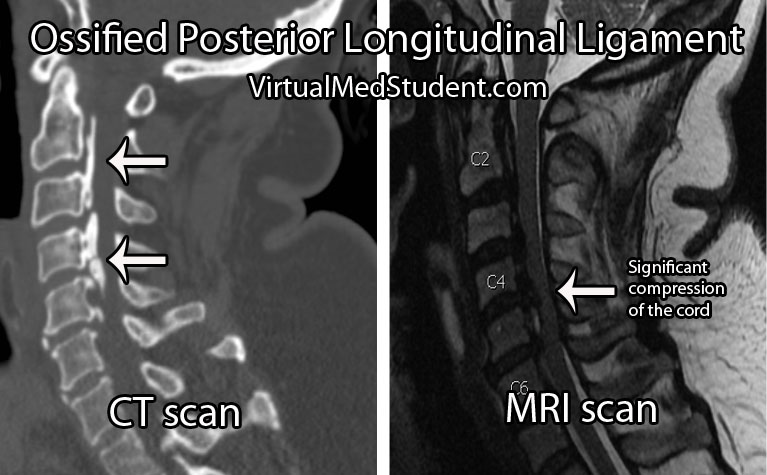

Imaging studies such as xrays and CT scans illustrate the bony quality of the ligament. MRIs are frequently ordered to assess how "squashed" the spinal cord is. CT myelograms also provide excellent detail of cord compression when MRI is not feasible.

The ossification is classified according to its anatomic location and continuity. There are four distinct patterns. They include a continuous pattern, in which there is ossification behind both the vertebral bodies and the disc spaces. The second pattern is known as segmental; in this type the ossification is only present behind the vertebral bodies and does not span the disc spaces. The third pattern is localized, which means that the ossified ligament is present and localized behind only one vertebral body. Finally, there is a mixed type, which is a combination of continuous and segmental.

Treatment

The problem with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament is that it progresses over time. Slowly, the ligament will compress the spinal cord. Therefore, surgical treatment is typically offered at the first sign of spinal cord compression (ie: myelopathy).

The best surgical treatment is controversial. Approaching the spine from the front (ie: anterior approach) allows direct removal of the ossified ligament. However, it is important to note that the ligament is often stuck to the dura mater overlying the spinal cord which can make dissection extremely difficult. A cerebrospinal fluid leak is not uncommon when an anterior approach is taken, and there is an increased risk of inadvertent injury to the spinal cord. That being said, when successful, surgery from the front offers several distinct advantages. The first is that myelopathic symptoms seem to respond better to this type of approach; in addition, removal of the ossified ligament can retard further progression of the disease.

The second surgical option is to approach the spine from the back (ie: posterior approach). Removing the bone behind the spinal cord allows the cord to "drift" backwards away from the ossified ligament. This approach is considered more safe because there is no direct removal of the ossified ligament, and therefore there is a decreased risk of inadvertent cord injury. That being said, progression of the ossification can still occur and myelopathic symptoms do not respond as well to this type of surgery.

Ultimately, the type of surgery offered – anterior versus posterior – is dictated by the severity of the ossification and symptoms present, as well as the preferred approach of the surgeon.

Overview

Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament is seen more commonly in patients of Japanese descent. There are genetic factors that appear to increase risk. Symptoms are related to compression of the spinal cord by the ossified ligament. Ossification is progressive in nature. Treatment consists of surgery from either an anterior, posterior, or combined approach.

Related Articles

- Atlas fractures

- Os odontoideum

- Three column spine

- Hangman’s fracture

- Dislocated cervical facets

- Odontoid fractures

References and Resources

- Maeda S, Ishidou Y, Koga H, et al. Functional impact of human collagen alpha2(XI) gene polymorphism in pathogenesis of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine. J Bone Miner Res. 2001 May;16(5):948-57.

- Sakou T, Matsunaga S, Koga H. Recent progress in the study of pathogenesis of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. J Orthop Sci. 2000;5(3):310-5.

- Fargen KM, Cox JB, Hoh DJ. Does ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament progress after laminoplasty? Radiographic and clinical evidence of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament lesion growth and the risk factors for late neurologic deterioration. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012 Dec;17(6):512-24.

- Akune T, Ogata N, Seichi A, et al. Insulin secretory response is positively associated with the extent of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001 Oct;83-A(10):1537-44.

- Epstein N. Diagnosis and surgical management of cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine J. 2002 Nov-Dec;2(6):436-49.