The three column model of the spine was first introduced by Dr. Francis Denis in his aptly named paper, "The Three Column Spine and its Significance in the Classification of Acute Thoracolumbar Spinal Injuries". This paper, published in 1983, proposed a new biomechanical model for spinal stability that challenged Dr. Frank Holdsworth’s two column model from the 1960s. Although replaced by more modern grading scales (ie: the TLICS model) the three column spine is a simple way to think about spinal biomechanics.

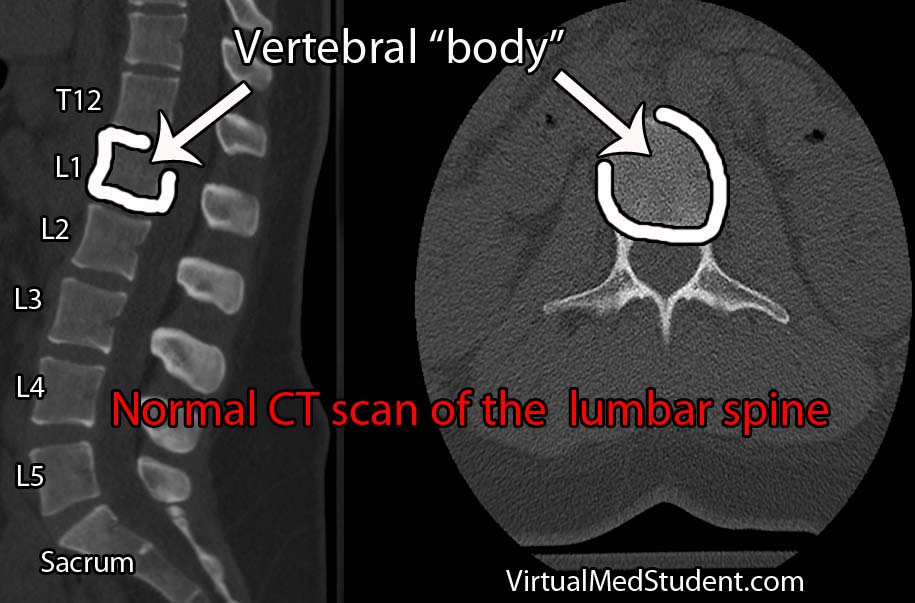

Denis’ three column model proposes that the thoracolumbar spine can be divided into three columns. The first column includes the anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL) up to the first half of the bony vertebral body. The second column includes the second half (ie: more posterior half) of the vertebral body, up to, and including the posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL). The third column includes the pedicles, spinal cord/thecal sac, lamina, transverse processes, facet joints, spinous process, and the posterior ligaments (ie: supraspinous, interspinous, and ligamentum flavum).

The purpose of Denis’ model was to delineate which injuries to the thoracolumbar spine were considered "unstable". This delineation was important because it determined which patient’s required operative treatment of their spine.

Simply stated, an unstable spine was present if two or more of the columns were involved in the injury. However, it is important to note that every rule can be broken, so not all injuries follow this rule. Part of the "art" of practicing spine surgery is determining which two-column injuries can be left alone and managed non-operatively, and which truly require operative intervention.

Types of Injuries

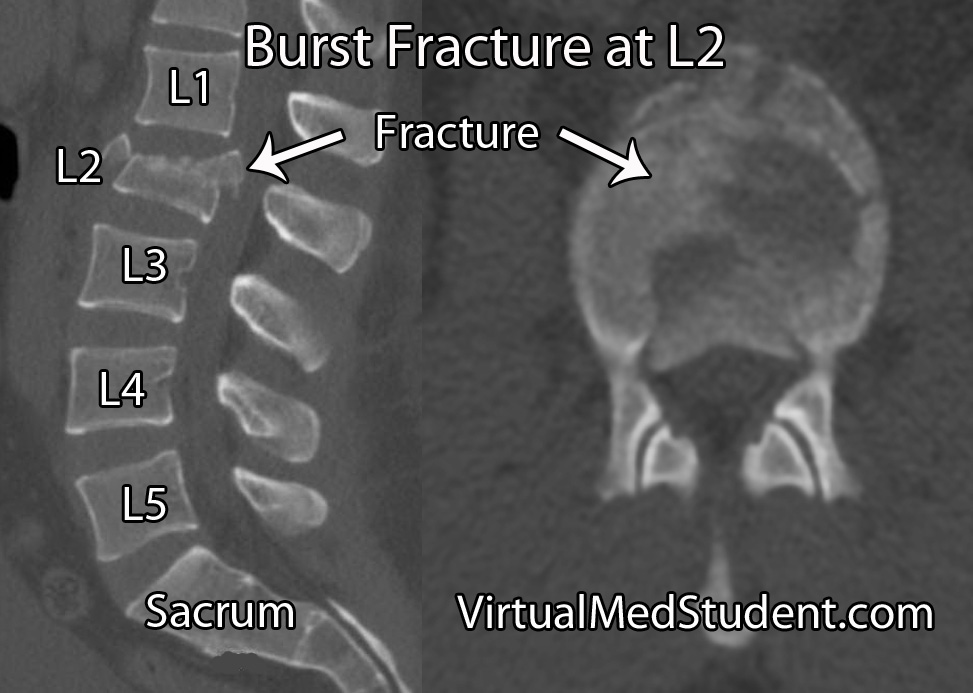

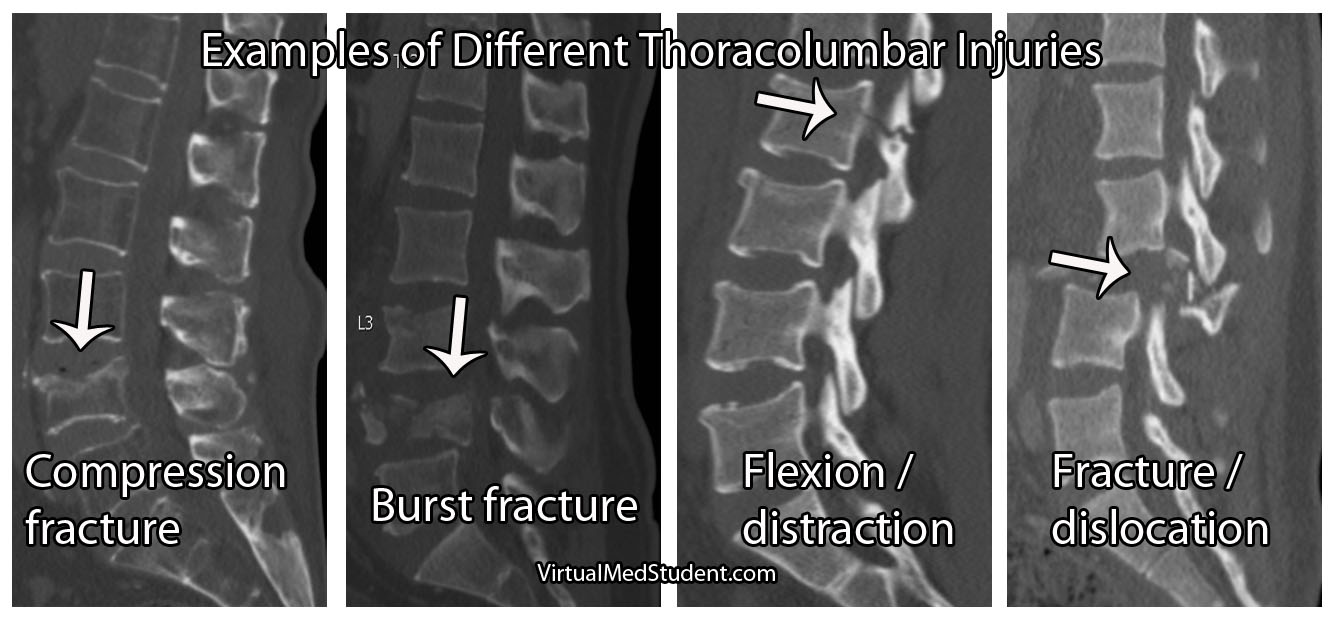

Based on Denis’ model he classified specific types of injuries. Injuries to the anterior column only were called "compression fractures". Damage to the anterior and middle columns were known as "burst fractures". Injury to the middle and posterior column were known as "flexion-distraction" injuries, or more colloquially as "seat-belt type" injuries. Finally, damage to all three columns were classified as "fracture-dislocation" injuries.

Classification of Thoracolumbar Injuries Using the Three Column Model |

||

| Columns | Name | Stability |

| Anterior | Compression fracture | Stable |

| Anterior and Middle | Burst fracture | Unstable |

| Middle and Posterior | Flexion-distraction injury (aka: seat-belt type) | Unstable |

| Anterior, middle, and posterior | Fracture-dislocation | Unstable |

Clinical Significance

In very simple terms, unstable fractures require definitive treatment. Treatment for unstable spine injuries is usually operative, although rigid immobilization with bracing is sometimes used in certain circumstances.

The treatment of each fracture type is beyond the scope of this article (and discussed in more detail elsewhere on this site), but suffice it to stay that for the most part (and again, every rule was made to be broken) two or three column injures = unstable = surgery.

Overview

Denis’ three column model of the spine revolutionized the way we think about spinal biomechanics and stability. He divided the spine into three columns. Although it has been largely replaced by more modern grading scales such as the thoracolumbar injury classification and severity score (TLICS) it is still a nice way to “think” about spinal integrity.

Other Common Spine Injuries…

References and Resources

- Denis F. The three column spine and its significance in the classification of acute thoracolumbar spine injuries. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1983 Nov-Dec;8(8):817-31.

- Denis F. Spinal instability as defined by the three-column spine concept in acute spinal trauma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984 Oct;(189):65-76.

- Lewkonia P, Paolucci EO, Thomas K. Reliability of the Thoracolumbar Injury Classification and Severity Score and comparison to the Denis classification for injury to the thoracic and lumbar spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012 May 29.

- Lenarz CJ, Place HM, Lenke LG, et al. Comparative reliability of 3 thoracolumbar fracture classification systems. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2009 Aug;22(6):422-7.

- Greenberg MS. Handbook of Neurosurgery

. Sixth Edition. New York: Thieme, 2006. Chapter 25.