Hemangiopericytomas can occur anywhere blood vessels are located, but are most commonly located in the lower extremities, pelvis, head, and neck.

Intracranial hemangiopericytomas are uncommon. They represent less than 1% of tumors within the confines of the skull. They typically arise from blood vessels adjacent to the dura (ie: lining of the brain) and often form dural attachments. They are therefore commonly lumped into the category of “dural-based tumors”, but should be distinguished from their more benign meningeal cousins (ie: meningiomas).

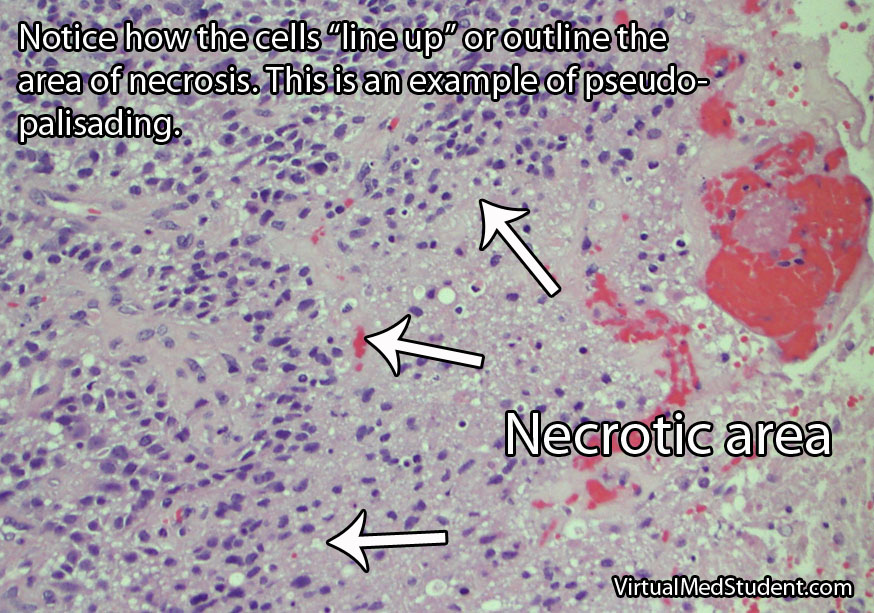

Since hemangiopericytomas are mesenchymal in origin, they typically have lots of reticulin (a collagen fiber) that envelopes individual cells (see pathology slide). They are highly cellular tumors, and vascular channels in the shape of "staghorns", may be seen under the microscope. Actively dividing cells (aka: "mitotic" figures) are commonly seen and are a testament to their more malignant nature. Unlike meningiomas, calcifications are absent.

Hemangiopericytomas test positive for vimentin (a marker of connective tissue), Ki-67 (a marker of proliferation), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF, a marker of blood vessel proliferation), CD34 (a marker of blood and vascular cell lineage), and reticulin (a collagen fiber). These tumors do not stain positive for epithelial membrane antigen. Genetic mutations have been found on different chromosomes , but the importance of these abnormalities is not well understood.

Intracranial hemangiopericytomas are considered malignant tumors. This means that they can spread to other areas of the body. In addition, hemangiopericytomas that have been removed surgically have a high recurrence rate.

Signs and Symptoms

Hemangiopericytomas are relatively slow growing and often do not cause symptoms until they become quite large. However, once they start to compress adjacent brain tissue they may cause headaches, seizures, confusion, weakness, or visual problems.

Diagnosis

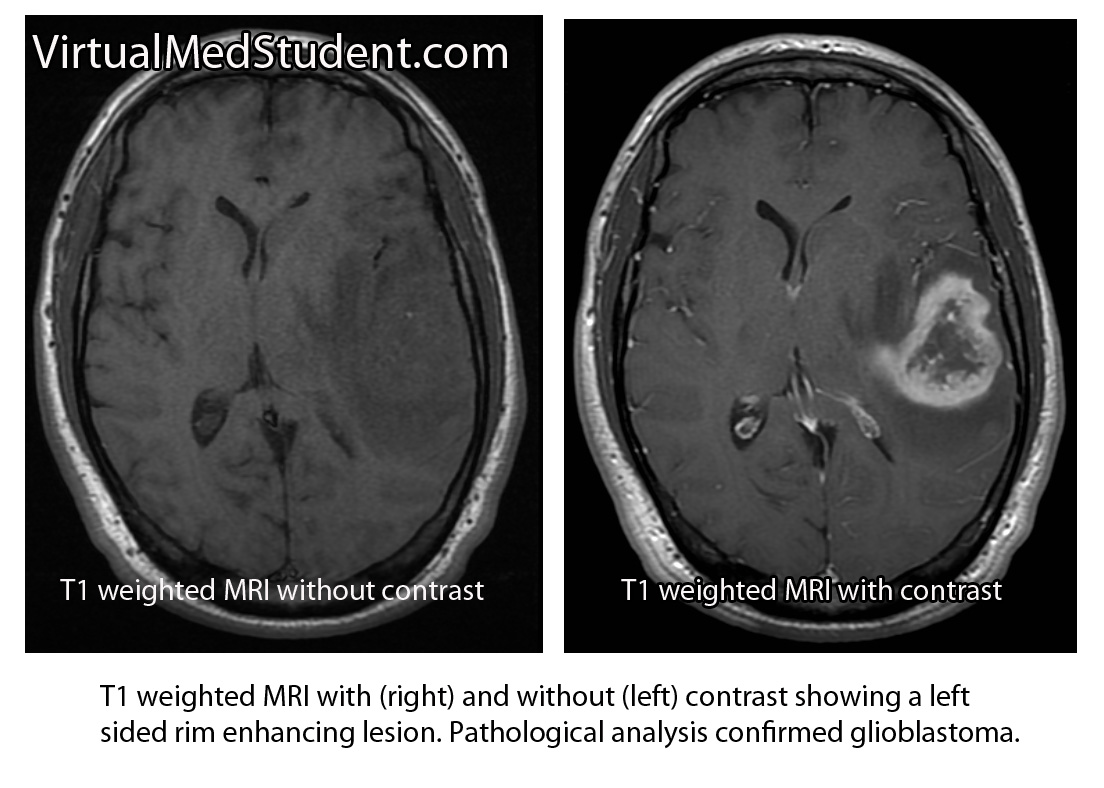

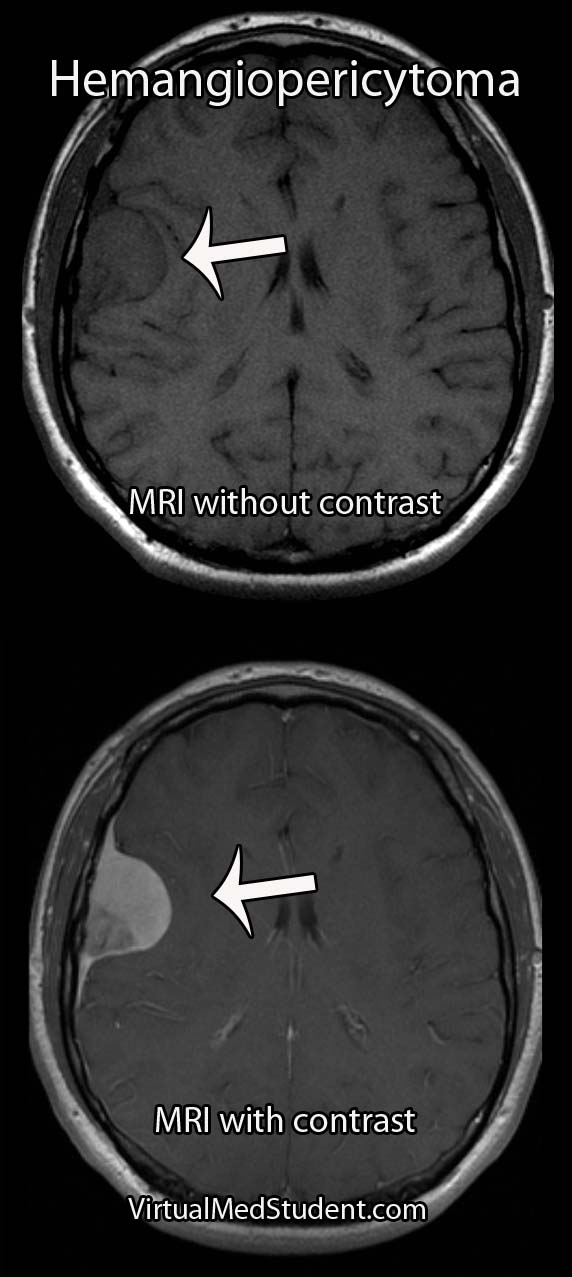

MRIs and CT scans of the brain typically reveal a contrast enhancing dural-based lesion. Cerebral angiograms show a highly vascular tumor with blood supply coming from the dura, as well as the underlying brain tissue.

The only reliable way to diagnose hemangiopericytoma is to look at a specimen of the tumor under a microscope. Special stains and features of the tumor can help delineate it from a meningioma (see pathology section above).

Did I Hear Someone Say “Treatment”?

Intracranial hemangiopericytomas should be surgically resected when feasible. Unfortunately, even after complete resection, they frequently recur and/or spread to other areas of the body.

Because of their aggressive nature, patients with hemangiopericytomas should also have adjuvant radiation therapy. Radiation treatment after surgical removal of the tumor has been shown to lengthen survival and slows (but doesn’t appear to prevent) the time to recurrence.

The role of chemotherapy is less clear and is still being investigated. At this point, chemotherapy is typically used in patients where radiation and surgery have failed to control the disease.

Let’s Recap It…

Intracranial hemangiopericytomas are malignant dural-based tumors that arise from pericytes. They are highly vascular tumors that enhance on MRI and CT scans. Symptoms are variable and depend on the size and location of the tumor. Treatment is with surgical removal followed by radiation therapy. Recurrence rates are high despite optimal treatment.

You Should Learn About This Stuff Too…

- Acoustic Neuroma: The Tumor Named Twice

- Cerebral Cavernous Malformations: Leaky Vessels

- Ependymoma: Myxopapillary, Anaplastic, and Pseudorosettes

- Glioblastoma: A Real Beast

- Colloid cyst of the third ventricle

- Medulloblastoma: Sonic Hedgehog, Wingless, and Prognosis

Want Some More?

- Marec-Berard P. Malignant hemangiopericytoma. Orphanet Encyclopedia. April 2004.

- Kumar N, Kumar R, Kapoor R, et al. Intracranial meningeal hemangiopericytoma: 10 years experience of a tertiary care Institute. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2012 Jul 12.

- Schiariti M, Goetz P, El-Maghraby H, et al. Hemangiopericytoma: long-term outcome revisited. Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2011 Mar;114(3):747-55.

- Kaye AH, Laws ER. Brain Tumors. New York: Churchill Livingston, 1995.

- Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. New York: WHO Publications Center, 2007.

- Olson C, Yen CP, Schlesinger D, et al. Radiosurgery for intracranial hemangiopericytomas: outcomes after initial and repeat Gamma Knife surgery. J Neurosurg. 2010 Jan;112(1):133-9.