Ependymomas are tumors that develop from cells known as ependymal cells (duh!). Ependymal cells are a type of glial cell that line the ventricles (ie: fluid filled cavities) of the brain and central canal of the spinal cord.

Normal ependyma have cilia and microvilli on the side of the cell that faces cerebrospinal fluid (ie: the "apical" side). Cilia are hair like extensions that are believed to "beat" cerebrospinal fluid around the ventricles. Microvilli are folds in the cellular membrane that are thought to aid in the reabsorption of cerebrospinal fluid.

Unlike other epithelial cells in the body, of which ependyma are considered a subgroup, they do not rest on a basement membrane. Instead their basal surfaces (the surface not in contact with cerebrospinal fluid) intertwine with the overlying brain tissue.

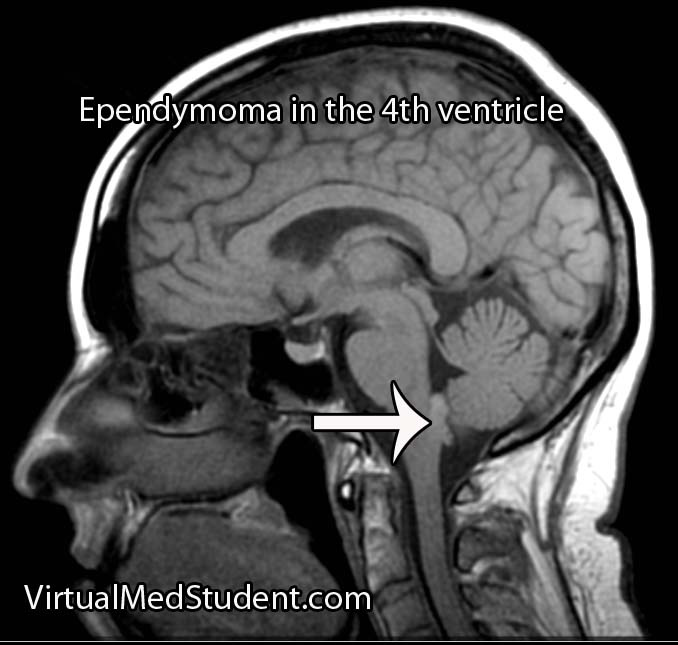

Like any other cell in the body, ependymal cells can decide to turn naughty and form a tumor. Ependymomas can occur anywhere there are ependymal cells, and therefore develop in both the brain and spinal cord. Intracranial ependymomas are more common in younger age groups, whereas spinal forms are more common in older individuals. Of those that form within the confines of the skull, the most common location is in the fourth ventricle near the brainstem.

There are three "grades" of ependymoma. There are two subsets of grade one: myxopapillary and subependymomas. The second grade of ependymoma has four distinct variants. They are cellular, papillary, clear cell, and tanycytic. The third grade is also referred to as "anaplastic" ependymoma. Regardless of the grade, each type has its own distinct characteristics when viewed under the pathology microscope.

Surgical specimens of ependymomas are often "stained" by pathologists to help aid in diagnosis, and more importantly, distinguish them from other tumor types. Ependymomas stain positive for the glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), as well as phosphotungstic acid hematoxylin (PTAH).

Ependymomas may have perivascular pseudorosettes, which helps support the diagnosis. Pseudorosettes may not be apparent in tumors with dense cellularity such as anaplastic ependymomas.

In addition, ependymomas can spread throughout the cerebrospinal fluid space. For example, a tumor that arises in the fourth ventricle may "drop" tumor cells down into the spinal cord forming a secondary tumor. These secondary tumors are referred to as "drop mets".

Signs and Symptoms

The signs and symptoms depend on the location of the ependymoma.

The most common symptom of intracranial ependymoma is headache associated with nausea and/or vomiting. These symptoms occur when the ependymoma blocks the flow of cerebrospinal fluid, which causes a condition known as non-communicative hydrocephalus.

You can think of non-communicative hydrocephalus as a clog in a pipe. Everything upstream of the clog starts to back up, which eventually leads to increasing pressures. When this increased pressure occurs in the ventricular system of the brain it causes worsening headaches, nausea, and vomiting. This is especially true if the ependymoma is in the fourth ventricle of the brain, which even without tumor, is an anatomically narrow "pipe" to begin with.

Additionally, if the tumor pushes on brainstem structures a patient may present with dysfunction of the nerves that go to the various muscles of the head and face. The most commonly involved nerves are the facial nerve, which can cause weakness of the face, as well as the abducens nerve, which can cause weakness of the eye.

Tumors located in the spinal cord cause weakness and sensory disturbances.

Diagnosis

MRI scans can be very useful and can support (but not prove) the diagnosis of ependymoma, especially when the tumor is in a common anatomical location.

If there is a high index of suspicion for ependymoma then the entire neuro-axis, meaning the brain and entire spinal column, should be imaged using MRI. This will detect “drop” mets, which, if present, further support the diagnosis.

Diagnosis can only be officially made when a sample of tumor (either surgical or at autopsy) is seen under the pathology microscope.

Treatment

Treatment of ependymoma is with surgical resection followed by radiation therapy. Patient outcome is most effective if the entire tumor can be removed during surgery. This is known as "gross total resection". However, the extent of surgical resection should always be weighed against the risk of harming the patient, especially if the tumor has invaded vital structures like the brainstem.

Fortunately, ependymomas are very radio-sensitive, which means that they respond well to getting zapped with radiation. Chemotherapy is not typically helpful except in very young children where the effects of radiation can be devastating.

Overview

Ependymomas arise from the cells that line the ventricular system of the brain and spinal cord. There are different subtypes depending on what it looks like under the pathology microscope. Diagnosis is based on pathological analysis and characteristic MRI findings. Treatment is with surgery and radiation.

Other Diseases You Should Know About…

- Acoustic neuroma

- Cavernous malformations

- Chordoma

- Colloid cysts

- Glioblastoma

- Hemangioblastoma

- Meningioma

- Hemangiopericytoma

References and Resources

- Pinho RS, Andreoni S, Silva NS, et al. Pediatric central nervous system tumors: a single-center experience from 1989 to 2009. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011 Dec;33(8):605-9.

- Macedo LT, Rogerio F, Pereira EB, et al. Cerebrospinal tumor dissemination in a patient with myxopapillary ependymoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Nov 10;29(32):e795-8. Epub 2011 Oct 11.

- Yao Y, Mack SC, Taylor MD. Molecular genetics of ependymoma. Chin J Cancer. 2011 Oct;30(10):669-81.

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease

. Seventh Edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2004.