Cardiomyopathy = cardio (heart) + myo (muscle) + pathy (pathology). In other words, cardiomyopathies are pathologic processes that affect the heart muscle. Dilated cardiomyopathy, which this article is about, is the most common form of cardiomyopathy. It has some known causes, but interestingly the majority of cases have no known cause and may in fact be inherited. In order to be diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy you must have left ventricular dilation and a low ejection fraction on echocardiography.

(1) Idiopathic (ie: no known cause) and/or genetic

(2) Alcoholism (chronic)

(3) Inflammatory

(a) Infectious

(i) Viral

1. Adenovirus

2. Coxsackie virus

3. Parvovirus

4. HIV

(ii) Protozoan

1. Trypanosomiasis (Chagas’ disease)

(b) Non-infectious

(i) Collagen vascular disorders

(ii) Sarcoidosis

(4) Drug/medicine related

(a) Chemotherapeutics (daunorubicin/doxorubicin)

(b) Cocaine

(c) Methamphetamines

(d) Heavy metals

(5) Metabolic

(a) Hypothyroidism

(b) Hypocalcemia (chronic)

(c) Hypophosphatemia (chronic)

(6) Neuromuscular diseases

Regardless of the cause, the left ventricle of the heart dilates, which decreases its ability to pump effectively.

Signs and Symptoms

The symptoms of dilated cardiomyopathy are directly related to the decreased pumping ability of the heart (ie: systolic dysfunction). Blood backs up into the rest of the body starting with the lungs. This causes pulmonary edema, which can manifest as orthopnea (ie: inability to sleep flat due to shortness of breath), dyspnea (ie: shortness of breath with exertion), and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (ie: waking up in the middle of the night short of breath). Patients also complain of exercise intolerance, dizziness, and fatigue.

The physical exam for someone with dilated cardiomyopathy will often reveal an S3 gallop (aka: ventricular gallop). An S3 gallop is caused by excess blood in the left ventricle after systole; during diastole the blood from the left atrium rushes into a relatively full left ventricle creating the S3 gallop, which can be heard with a stethoscope.

In addition, “crackles” may be heard in the lung fields secondary to pulmonary edema. If right sided heart failure has also occurred (usually after many years of left sided cardiomyopathy) there may be signs of systemic volume overload. These signs include hepatomegaly (a larger than normal liver), bilateral lower extremity edema (ie: pitting edema), and jugular vein distension.

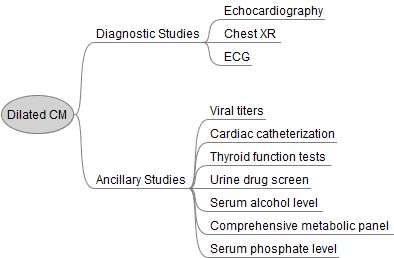

Diagnosis

Additional studies can be ordered depending on the clinical scenario. It is especially important to not miss alcoholism or hypothyroidism as these can be easily treated. Cardiac catheterization is often performed to determine if there is co-existing (or causative) coronary artery disease.

Treatment

Treatment for patients with dilated cardiomyopathy consists of the similar treatments used for other heart failure patients. Many patients will be on an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI, lisinopril is a commonly used one), or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) and a beta blocker (carvedilol is commonly used due to its beneficial lipid profile compared to other beta blockers). Other considerations include spironolactone (an aldosterone receptor antagonist).

ACEI/ARBs, beta blockers, and spironolactone improve survival rates in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. In addition, an implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD) should be considered in all patients with an ejection fraction of less than 35% because it has been shown to reduce death from abnormal heart rhythms.

Blood thinning medications like warfarin are indicated if the patient has a thrombus (ie: a “blood clot”) seen on echocardiogram, atrial fibrillation, or previous embolic event, although some physicians may recommend thinning the blood prophylactically if ventricular function is severely impaired (EF < 30%).

Symptomatic management consists of diuretics for volume overload (ie: pitting edema, shortness of breath secondary to pulmonary edema, etc.) and digoxin to increase cardiac contractility and improve forward blood flow.

Curative treatment is a heart transplant. Overall prognosis without a transplantation is poor. Over 50% of non-transplant patients are deceased at 5 years compared to 25% of transplanted patients.

Overview

There are many causes of dilated cardiomyopathy some of which are reversible. An S3 gallop and symptoms of volume overload are often seen on physical exam. Echocardiography is the gold standard for diagnosis. It is important to treat with at least a beta blocker and ACEI; spironolactone is another option. Symptomatic management includes diuretics and digoxin. Prognosis is poor without transplant.

Related Articles

- Restrictive Cardiomyopathy: Amyloid, Diastolic Dysfunction, and Kussmaul’s Sign

- Cardiac Output: Pump, Pump, Squeeze

- AV Heart Block: PR, QRS, and Mobitz

References and Resources

- Wexler RK, Elton T, Pleister A, et al. Cardiomyopathy: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2009 May 1;79(9):778-84.

- Abdo AS, Kemp R, Barham J, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy and role of antithrombotic therapy. Am J Med Sci. 2010 Jun;339(6):557-60.

- Fatkin D, Otway R, Richmond Z. Genetics of dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart Fail Clin. 2010 Apr;6(2):129-40.

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. Tenth Edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2004.

- Lilly LS, et al. Pathophysiology of Heart Disease: A Collaborative Project of Medical Students and Faculty. Seventh Edition. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2006.

- Flynn JA. Oxford American Handbook of Clinical Medicine (Oxford American Handbooks of Medicine). First Edition. Oxford University Press, 2007.